Steven Erlanger, The New York Times

STOCKHOLM — In a civic center in Rinkeby, a heavily immigrant district of northwest Stockholm, several hundred people gathered recently for a forum on Sweden’s coming election and the future of the country.

The conversation, about the nature of Sweden’s democracy and the importance of voting, was sophisticated and passionate. But it was frustrating for one participant, Ahmed Ali, a Somali immigrant, who thought people were dancing around the main issue.

“The stakes are really high in this election,” he said in an interview. “There are more extremists in the country, and they have more influence. They don’t have a real political agenda. They just hate immigrants. And this xenophobia is happening all over Europe.”

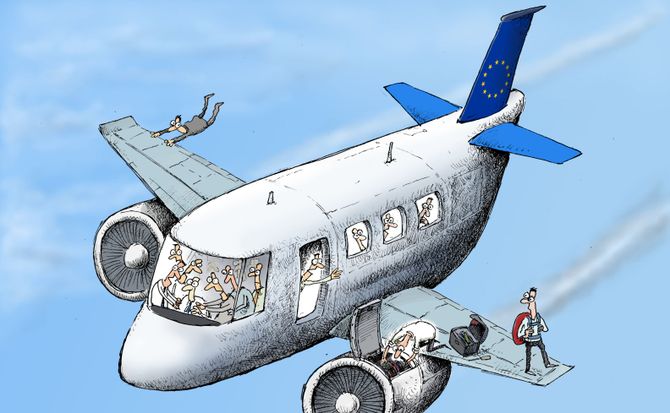

As an angry and divided Sweden prepares to vote on Sunday, the shape of the next Swedish government is utterly unclear, because of the rapid rise of the anti-immigration, anti-Europe Sweden Democrats, a populist nationalist party that is expected to win a fifth of the vote.

“This election is very important to us,” said Kahin Ahmed, 48, who is running for a local seat, but complains that none of the Swedish parties put immigrants or black people high enough on their party lists to get elected in proportionate numbers, even in areas like this one. “There is a racist party moving forward fast, and we have to stop them.”

Sweden, long considered “a moral superpower,” as the political scientist Lars Tragardh put it, has traditionally welcomed immigrants. But that is changing under the pressure of globalization, immigration and anxiety about national and cultural identity. As in Germany and France, parties of the extremes, of the left and especially of the right, are increasing their support at the expense of those that have traditionally dominated.

Sweden “is joining the rest of Europe,” Carl Bildt, a former prime minister from the center-right Moderate Party, said with evident sadness. “And the myth of the Sweden model is melting away.”

The melting was in evidence recently in Sergels Square in central Stockholm, where Martin Westmont, a candidate for the Stockholm regional council, made the Sweden Democrats’ case to the voters.

“We’re the new wave,” he said. The election “will be a revolution.” He predicted that the Social Democrats, the party who built the famous Swedish welfare state, would collapse, “even if not this time,” and “we will become the largest party.” Many voters were still reluctant to tell pollsters that they would vote for the Sweden Democrats, Mr. Westmont suggested.

Populism has shifted the political discourse to the right and raised the temperature, even among the traditionally phlegmatic Swedes. Political support is fragmenting, with the long-dominant Social Democrats heading for their worst showing in a century.

They are losing voters to the Left Party and the Greens, especially after this summer of extensive forest fires, but also some working-class voters to the far-right Sweden Democrats. The Moderates have lost even more to the far right.

The migrant wave of 2015 flowed mostly to Germany and Sweden, regarded as Europe’s most welcoming nations. Germany took in more than one million, while 163,000 arrived in Sweden seeking asylum, a large number in a country of 10.1 million. If the panic in Sweden has been less than in Germany, the political impact has been similar: the rise of a far-right, anti-immigrant, nationalist party — Alternative for Germany in one case, and the Sweden Democrats in the other — that is upending old certainties.

Political elites here as elsewhere “underestimated how much people still live in national democracies,” not some global stew, said Professor Tragardh, who teaches at Ersta Skondal Bracke University College.

As in Germany, stiffer border controls were quickly introduced in Sweden and the numbers of new immigrants fell steeply, to about 23,000 this year. But the political damage had been done, and despite a thriving economy and low unemployment, the Sweden Democrats argue that immigration should stop and that resources should go to refurbishing the welfare state strained by an aging population, gang violence and the challenge of taking on migrants.

Integration of newcomers takes up to seven years, because of tough labor market requirements, insisted upon by Sweden’s trade unions, and the challenges of the country’s language and of its culture, which is more comfortable opening its borders than its homes.

“This election really matters, and it is pretty much up in the air,” said Jonas Hinnfors, a professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg. Welfare, health and taxes are, as ever, top issues, as is climate change, he said, but “to an unprecedented extent, you have immigration and crime, and also unprecedented is the way the Social Democrats are campaigning on these issues and proposing more police and tougher border controls.”

The rise of the Sweden Democrats masks the decline of the Social Democrats, who are synonymous with social democracy in Europe and have come first in nearly every Swedish election since 1917. But while they got over 50 percent of the vote in 1968 and more than 45 percent in 1994, their support has dwindled steadily to about 25 percent, reflecting declines in support for socialist and left-center parties elsewhere in Europe.

If the Sweden Democrats, as expected, get around 20 percent of the vote, that will make it impossible for either the center-left or center-right bloc to form a majority government. The other parties insist that they will not do any deals with the Sweden Democrats, but the question has already cost the Moderates one leader and is bound to come up again in the days after the election, no matter which bloc ends up larger.

The surge of the Sweden Democrats, with their roots in Swedish fascism and neo-Nazism, has astounded many. Under a young leader, Jimmie Akesson, the party has moved to expel its most extreme members and soften its message, symbolized by the switch of its logo from a flaming torch to a floppy version of the blue anemone, one of Sweden’s favorite flowers and a harbinger of spring.

The strategy seems to be working. The party crossed the 4 percent threshold for parliamentary seats in 2010, getting 5.7 percent of the vote; in 2014, it won 12.9 percent. It could now become Sweden’s second-largest party, with all the complications that could bring.

The Sweden Democrats have not abandoned their traditional slogan, “Keep Sweden Swedish,” but have downplayed it in favor of “Security and Tradition.” What they are selling, most people agree, is nostalgia for a mythic Sweden of the 1950s — safe, prosperous and white.

They vow to protect the civil religion of the welfare state and restore the “Folkhemmet,” or the “people’s home,” the idea of the nation as a family where everyone contributes and cares for one another. That concept was created by the Social Democrats, but many consider it threatened by immigration, Islam and crime.

And like other populist parties across Europe, they have been greatly aided by the 2015 migration wave, a rise in gang warfare in the suburbs of big cities and some coordinated and highly visible bouts of car burnings.

Mr. Westmont, 39, the Sweden Democrats’ candidate for the Stockholm regional council, said his experiences growing up were typical of many in his generation who have soured on immigration.

He said he was a youth member of the center-right Moderates, “but they were becoming too liberal for me.” Growing up in a Stockholm suburb, “half the kids” were immigrants. “So I saw the problem from an early age, and I also saw that what the other parties say was not true.”

When he joined the Sweden Democrats in 2010, his parents were so embarrassed that he decided to change his name, he said. “But a lot of Moderates have come to us, and now my father supports the party, and I hope my mother will, too.” Then he smiled and said, “But who knows about mothers?”

Kimia Khodabandeh sees a more sinister side. Age 18 and a first-time voter, she was born in Sweden to Iranian parents who fled the revolution there. “I do feel targeted,” she said. “I was raised Swedish and feel Swedish, but I don’t look Swedish, and they wouldn’t accept us as Swedish.”

“And that’s why I’m concerned,” she continued. “We live in a society where everyone is accepted and helps one another, but we’re heading in the wrong direction. I just don’t understand why some people want to ruin everything.”

In the end, the Social Democrats and the center left may yet cling to power, and the Sweden Democrats may do well but again be kept out of the government. But the question of whether to make some deal with them, as mainstream parties in Finland, Denmark and Norway have done with their far-right rivals, or to continue to isolate them, is unlikely to go away.

“This election is a struggle about values and Swedish identity,” said Ulf Bjereld, a professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg and an active member of the Social Democrats. “The question is how to keep Sweden in the forefront of liberalism and social democracy versus stronger support for the nation state and borders. Who will Sweden be in this struggle? We’re just at the beginning of this debate.”

The solution to Europe’s weakness is not more government programs but letting market forces work

The solution to Europe’s weakness is not more government programs but letting market forces work

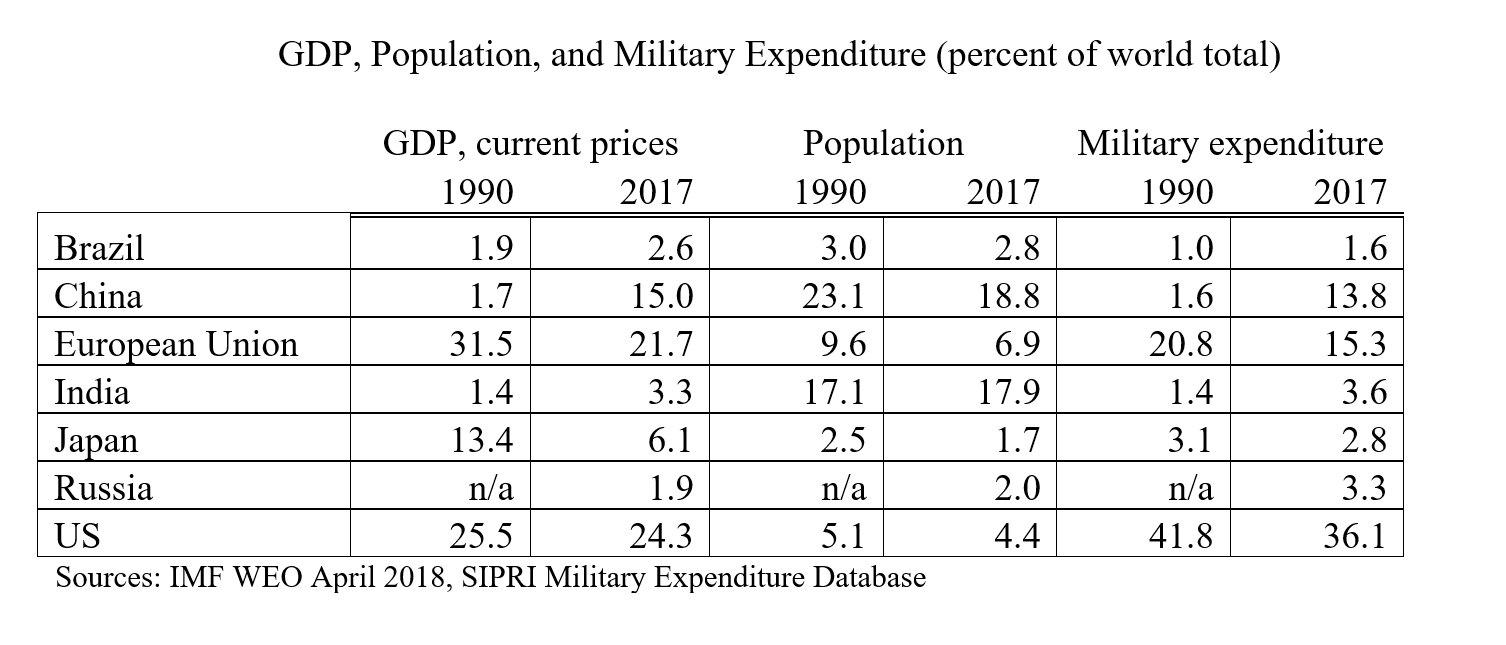

CAMBRIDGE – In July, I joined 43 other scholars of international relations in paying for a newspaper advertisement arguing that the US should preserve the current international order. The institutions that make up this order have contributed to “unprecedented levels of prosperity and the longest period in modern history without war between major powers. US leadership helped to create this system, and US leadership has long been critical for its success.”

But some serious scholars declined to sign, not only on grounds of the political futility of such public statements, but because they disagreed with the “bipartisan US commitment to ‘liberal hegemony’ and the fetishization of ‘US leadership’ on which it rests.” Critics correctly pointed out that the American order after 1945 was neither global nor always very liberal, while defenders replied that while the order was imperfect, it produced unparalleled economic growth and allowed the spread of democracy.

Such debates are unlikely to have much effect on President Donald Trump, who proclaimed in his inaugural address that, “From this day forward, it’s going to be only America First, America First […] We will seek friendship and goodwill with the nations of the world – but we do so with the understanding that it is the right of all nations to put their own interests first.”

But Trump went on to say that “we do not seek to impose our way of life on anyone, but rather to let it shine as an example.” And he did have a point. This approach can be called the “city on the hill” tradition, and it has a long pedigree. It is not pure isolationism, but it eschews activism in pursuit of values. American power is, instead, seen as resting on the “pillar of inspiration” rather than the “pillar of action.” For example, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams famously proclaimed on Independence Day in 1821 that the United States “does goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

But the soft power of inspiration is not the only ethical tradition in American foreign policy. There is also an interventionist and crusading tradition. Adams’s speech was an effort to fend off political pressure from those who wanted the US to intervene on behalf of Greek patriots rebelling against Ottoman oppression.

That tradition prevailed in the twentieth century, when Woodrow Wilson sought a foreign policy that would make the world safe for democracy. At mid-century, John F. Kennedy called for Americans to make the world safe for diversity, but he also sent 17,000 American military advisers to Vietnam. Since the end of the Cold War, the US has been involved in seven wars and military interventions, and in 2006, after the invasion of Iraq, George W. Bush issued a National Security Strategy that was almost the opposite of Trump’s, promoting freedom and a global community of democracies.

Americans often see their country as exceptional, and most recently President Barack Obama described himself a strong proponent of American exceptionalism. There are sound analytical reasons to believe that if the largest economy does not take the lead in providing global public goods, such goods – from which all can benefit – will be under-produced. That is one source of American exceptionalism.

Economic size makes the US different, but analysts like Daniel H. Deudney of Johns Hopkins University and Jeffrey W. Meiser of the University of Portland argue that the core reason that the US is widely viewed as exceptional is its intensely liberal character and an ideological vision of a way of life centered on political, economic, and social freedom.

Of course, right from the start, America’s liberal ideology had internal contradictions, with slavery written into its constitution. And Americans have always differed over how to promote liberal values in foreign policy. According to Deudney and Meiser,

“For some Americans, particularly recent neo-conservatives, intoxicated with power and righteousness, American exceptionalism is a green light, a legitimizing rationale, and an all-purpose excuse for ignoring international law and world public opinion, for invading other countries and imposing governments […] For others, American exceptionalism is code for the liberal internationalist aspiration for a world made free and peaceful not through the assertion of unchecked American power and influence, but rather through the erection of a system of international law and organization that protects domestic liberty by moderating international anarchy.”

Protected by two oceans, and bordered by weaker neighbors, the US largely focused on westward expansion in the nineteenth century and tried to avoid entanglement in the struggle for power then taking place in Europe. Otherwise, warned Adams, “The frontlet upon her brows would no longer beam with the ineffable splendor of freedom and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an imperial diadem, flashing in false and tarnished lustre the murky radiance of dominion and power.”

By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, America had replaced Britain as the world’s largest economy, and its intervention in World War I tipped the balance of power. And yet by the 1930s, many Americans had come to believe that intervention in Europe had been a mistake and embraced isolationism. After World War II, Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman – and others around the world – drew the lesson that the US could not afford to turn inward again.

Together, they created a system of security alliances, multilateral institutions, and relatively open economic policies that comprise Pax Americana or the “liberal international order.” Whatever one calls these arrangements, for 70 years it has been US foreign policy to defend them. Today, they are being called into question by the rise of powers such as China and a new wave of populism within the world’s democracies, which Trump tapped in 2016, when he became the first candidate of a major US political party to call into question the post-1945 international order.

The question for a post-Trump president is whether the US can successfully address both aspects of its exceptional role. Can the next president promote democratic values without military intervention and crusades, and at the same time take a non-hegemonic lead in establishing and maintaining the institutions needed for a world of interdependence?