The COVID-19 crisis has underscored the need for an entirely new approach to how we produce and consume. While Environmental, Social, and Governance standards of corporate risk disclosure are a necessary first step, the next should be unified metrics enabling assessment and comparison of companies’ wider impact on the world.

Europe in the World: for a Modest and Effective Reform

Editorial, December 16, 2020

This sad year ends with a pandemic that continues in full swing over a large part of the planet, especially in the United States and Europe, with no other reassuring prospect than that of one or more vaccines, which is already a lot. But that’s not the subject I want to focus on in this eighth letter, the last one for 2020. Internationally, two other facts have dominated the scene in recent months.

The first is the major turning point of the West vis-à-vis China, in the wake of Donald Trump’s offensive against Xi Jinping. Even in 2019, Europeans weren’t thinking in terms of a “Chinese threat”, even if many were beginning to worry about Chinese groups taking over a growing number of technology companies on the old continent. The deterioration in perceptions became evident during the tour of Minister Wang Yi and State Councillor Yiang Jiechi at the end of the summer. Certainly, the emergence of a sense of fear vis-à-vis the Middle Kingdom is also due to the change in tone of the Chinese leadership since the accession of Xi Jinping and the consolidation of his power. China’s leadership no longer hesitates to assert its desire for power beyond a mollifying discourse on the virtues of multilateralism, at a time when the United States was becoming more and more unilateral.

The second fact is obviously the election of the Biden-Harris tandem as President/Vice-President of the United States (as in my last letter, I insist on this notion of tandem), of which we can expect a return to good manners in the United States’ conduct of its foreign policy, but certainly not a softening in the face of China. Some, like my illustrious friend Joe Nye, a great artisan of concepts among which soft power has gained wide acceptance among political scientists, want to believe in the possibility of competitive rivalry, without major conflict over time around issues, the main one being Taiwan. I fear this will be wishful thinking, at least if China’s technological and economic rise continues to the point where the United States will soon be relegated to the second most powerful world power. Already the technological decoupling between the two superpowers has started.

The prospect of a deepening new Cold War is not just a concern for Europeans. I was able to see directly, in recent high-level meetings (virtual, unfortunately) with mostly Asian participants, that many countries in East and South-East Asia do not want to be forced to choose between the United States and China. They expect the same attitude from Europe. The warning is clear, and under the circumstances it is directed primarily to Washington. Realists are also wary of the strong inclination among American Democrats, but not just them, to play with the idea of regime change under the pretext of defending human rights. In Europe, this inclination is arguably the most fundamental reason for the failure of reconciliation with Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union. Be that as it may, the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a vast free trade agreement – heavily supported by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries – including China, Japan and South Korea, is a strong signal. The absence of India also weakens the geopolitical concept of an Indo-Pacific entity to counterbalance the Chinese space.

But it is above all from the European point of view that I would like to place myself. It is quite clear that the members of the European Union remain committed to the Atlantic Alliance, even though its purpose has lost all clarity since the fall of the Soviet Union. Questioning North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is taboo in Germany, where they do not want to hear talk about “strategic autonomy”. Germany is wary of France’s rhetoric and notes its economic weakness, which has only worsened with the pandemic. A member state like Poland sees a threat only from the Russian side and for many members the Alliance’s raison d’être has not changed with the end of the Cold War. However, I do not yet know anyone among my European contacts who is not aware of the risk of seeing the Atlantic Alliance gradually transforming, under American pressure, into an anti-Chinese alliance. In other words, no more than the Asians, Europeans as a whole do not want to be forced to choose between the two rivals from the outset, even if they have good reasons to lean towards the American side.

Concretely, we do not want the United States to continue abusing the devastating practice of secondary sanctions. These sanctions aim to wring the very necks of their allies, if they do not fully align with the United States’ policies (e.g., vis-à-vis Iran).

European construction is a long-term endeavour, where everything canot be accomplished at once. At the moment, a big step forward is being taken with the concept of technological sovereignty, now recognised by Germany itself and which seems to me could replace the concept of strategic autonomy, whose connotations divide. European sovereignty will only truly take shape if it is supported by a discourse shared by all members of the Union, which cannot happen overnight. I am convinced – and here I am speaking as a French citizen – that the best that we can do now is to reconnect with the humble and practical spirit of our compatriots Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet in the post-war years. They wanted to lay the foundations for European construction, not by waxing lyrically with no follow through, but based on projects – at the time, the European Coal and Steel Community – aimed at fostering the emergence of the idea of European interests, transcending the classic notion of national interest. Now, isn’t this exactly what the Commission chaired by Ursula von der Leyen is working on, by promoting the very concrete project of a technological Europe, to which Thierry Breton and others are committed? This is a well-defined task, which offends no one and is a prerequisite for any other ambition, albeit a long-term one. But its success is within our reach and will ultimately be our collective best chance to help restore a global balance that Europeans and others aspire to.

I would like to end on a note of optimism, by sending all of you my warmest wishes for 2021, for which we all expect a kind of rebirth.

Thierry de Montbrial

Founder and Chairman of the WPC

Founder and Executive Chairman of Ifri

The Biden-Harris election: a respite in view of what?

Editorial, November 8, 2020

I am writing this seventh letter on Sunday, November 8. Yesterday, the world press proclaimed the victory of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. However, Donald Trump has filed lawsuits in several states, which few people believe have any chance of succeeding. At this point, then, the present occupant of the White House can be said to have joined the narrow circle of one-term presidents. Other immediate observations come to mind. The Blue Wave heralded by the polls failed to materialize. Not only that, but Biden beat his opponent by a razor’s edge in the swing states, hence those lawsuits. The Democrats fell short of their goals in the Senate and the House of Representatives. There is more talk about the triumph of the Biden-Harris team than the success of one man, who led a lethargic campaign. This is a key point, for the new president looks frail and odds are that California’s former Attorney General will move into the White House in four years, if not before.

However, unlike his former opponent in the primaries, Ms. Harris psychologically belongs to the New World, far from Europe but close to Asia, where the competition for global supremacy between the United States and China is being played out. In that world, Europeans might be relegated to supporting roles. Because of his age and personal experience, the president-elect remains attached to the Atlantic Alliance, as do some of his advisors, such as Anthony Blinken, who is well known in France. But clear-headed observers are aware that, since at least the beginning of this century, Europe has steadily faded in the minds of American foreign policy-makers. I will add two more remarks before dipping into that topic. First, the November 3 election’s outcome does not by any stretch of the imagination mean that the rifts in American society have been healed. The 46th president of the United States is undeniably a man of good will but he is not a magician, far from it, and the reasons for America’s divisions, which I talked about in my last letters, run deep. Incidentally, the Democrats’ relative failure in the Senate and the House of Representatives could help the new president hew to the center, as Kamala Harris would not like him to do. The really important point is that Trumpism remains a force to be reckoned with in the US. Trump himself could continue to embody it in the next few years if he does not go off the rails in the next few weeks. In that regard—and this is my second remark—I am pleased to say that the outbreaks of violence predicted by many analysts in the election’s aftermath did not occur. True, that would not be in the outgoing president’s interests, if he is at least thinking of preserving his political capital, whose magnitude is undeniable.

Obviously, the Covid-19 pandemic and its multi-faceted consequences will overshadow the beginning of Biden’s first term. But foreign policy will not wait. There is no need to repeat here the dominant point of view among recognized experts on the subject, which could be caricaturized like this: a change in form (a return to classic diplomacy, the invocation of human rights and a minimalist interpretation of multilateralism) but continuity in the basic goal (“America First”) and the attitude towards partners (“you’re either with us or against us”). America’s culture of power, unlike Europe’s, weakened by two world wars, is based on strength. Rather than repeating commonplaces on these issues, let us summarize, in very broad strokes, three key points amply developed in my writings for three decades. Here I will limit myself to the European perspective.

- The most basic cause of the fall of the USSR, and therefore the end of the Cold War, was the information and communication technology revolution. This can be seen as the fruit of America’s genius for capitalism and a unique culture of mutual support between the State and companies when the national interest is at stake. That revolution has steadily gathered pace since the 1970s. Today it is symbolized by GAFA, which in a way can be considered the Trojan horse of American dominance.

- The liberal wave that submerged the world between the fall of the USSR and the financial crisis in the late 2000s, when Russia was sidelined or very weak and China still had a small economy (its GDP barely equaled that of France when it joined the WTO in 2001), first benefitted the United States, which was able to consolidate its domination over countries that cared little about national independence. That was the case of Europe, now subject to the extraterritoriality of American laws. But China also benefited. An extraordinary push in the education sector has allowed that country to skillfully use its position as a global reservoir of low-cost labor to achieve the massive technology transfers that have made its access to primacy in the 21st century a serious possibility.

- The basic reality of the next several decades will be Sino-American strategic competition, towards which the second-rank powers, like the European Union as a political unit, will have to position themselves. Trump wanted to pull out of NATO. Biden will undoubtedly want to strengthen it, i.e., in his mind, to politically and economically rally its members behind the star-spangled banner in the fight to contain China. For Europeans, who are hardly eager for a strategic rapprochement with China and who, unlike the main Asian powers, are lagging behind in the technological race, the temptation to put themselves under an American protectorate even more than they did during the Cold War could be irresistible. But with what term-long perspective and under what conditions with respect to their nearest neighbors in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa? That is the question.

For now, Europeans are relishing the election of a once-again empathetic American president who will warmly welcome them to the Oval Office and elsewhere. At a time when they are facing an invisible enemy that threatens them as well as Americans, they are not alone in yearning for a respite. May the Atlantic Alliance in the short term be the first alliance against the virus. For once in its history, do we not have an opportunity to reinterpret article five of the treaty and harness all of NATO’s resources to fight the pandemic together?

Thierry de Montbrial

Founder and Chairman of the WPC

Founder and Executive Chairman of Ifri

Joseph Nye: Can Joe Biden’s America Be Trusted?

Can Joe Biden’s America Be Trusted?

Project Syndicate – 04.12.2020

By Joseph S. Nye, JR.

America’s friends and allies have come to distrust it in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency. Joe Biden will do all that he can to repair the damage, but the deeper problem is that many are asking whether Trump was merely a symptom of the decline of American democracy.

CAMBRIDGE – Friends and allies have come to distrust the United States. Trust is closely related to truth, and President Donald Trump is notoriously loose with the truth. All presidents have lied, but never on such a scale that it debases the currency of trust. International polls show that America’s soft power of attraction has declined sharply over Trump’s presidency.

Can President-elect Joe Biden restore that trust? In the short run, yes. A change of style and policy will improve America’s standing in most countries. Trump was an outlier among US presidents. The presidency was his first job in government, after spending his career in the zero-sum world of New York City real estate and reality television, where outrageous statements hold the media’s attention and help you control the agenda.

In contrast, Biden is a well-vetted politician with long experience in foreign policy derived from decades in the Senate and eight years as vice president. Since the election, his initial statements and appointments have had a profoundly reassuring effect on allies.

Trump’s problem with allies was not his slogan “America First.” As I argue in Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump, presidents are entrusted with promoting the national interest. The important moral issue is how a president defines the national interest.

Trump chose narrow transactional definitions and, according to his former national security adviser, John Bolton, sometimes confused the national interest with his own personal, political, and financial interests. In contrast, many US presidents since Harry Truman have often taken a broad view of the national interest and did not confuse it with their own. Truman saw that helping others was in America’s national interest, and even forswore putting his name on the Marshall Plan for assistance to post-war reconstruction in Europe.

In contrast, Trump had disdain for alliances and multilateralism, which he readily displayed at meetings of the G7 or NATO. Even when he took useful actions in standing up to abusive Chinese trade practices, he failed to coordinate pressure on China, instead levying tariffs on US allies. Small wonder that many of them wondered if America’s (proper) opposition to the Chinese tech giant Huawei was motivated by commercial rather than security concerns.

And Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement and the World Health Organization sowed mistrust about American commitment to dealing with transnational global threats such as global warming and pandemics. Biden’s plan to rejoin both, and his reassurances about NATO, will have an immediate beneficial effect on US soft power.

But Biden will still face a deeper trust problem. Many allies are asking what is happening to American democracy. How can a country that produced as strange a political leader as Trump in 2016 be trusted not to produce another in 2024 or 2028? Is American democracy in decline, making the country untrustworthy?

The declining trust in government and other institutions that fueled Trump’s rise did not start with him. Low trust in government has been a US malady for a half-century. After success in World War II, three-quarters of Americans said they had a high degree of trust in government. This share fell to roughly one-quarter after the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal of the 1960s and 1970s. Fortunately, citizens’ behavior on issues like tax compliance was often much better than their replies to pollsters might suggest.

Perhaps the best demonstration of the underlying strength and resilience of American democratic culture was the 2020 election. Despite the worst pandemic in a century and dire predictions of chaotic voting conditions, a record number of voters turned out, and the thousands of local officials – Republicans, Democrats, and independents – who administered the election regarded the honest execution of their tasks as a civic duty.

In Georgia, which Trump narrowly lost, the Republican secretary of state, responsible for overseeing the election, defied baseless criticism from Trump and other Republicans, declaring, “I live by the motto that numbers don’t lie.” Trump’s lawsuits alleging massive fraud, lacking any evidence to support them, were thrown out in court after court, including by judges Trump had appointed. And Republicans in Michigan and Pennsylvania resisted his efforts to have state legislators overturn the election results. Contrary to the left’s predictions of doom and the right’s predictions of fraud, American democracy proved its strength and deep local roots.

But Americans, including Biden, will still face allies’ concerns about whether they can be trusted not to elect another Trump in 2024 or 2028. They note the polarization of the political parties, Trump’s refusal to accept his defeat, and the refusal of congressional Republican leaders to condemn his behavior or even explicitly recognize Biden’s victory.

The American Elections and Beyond

Éditoriaux de l’Ifri, October 12th, 2020

The next few years will be tumultuous ones in the United States. The dependency of foreign policy on domestic policy is unlikely to diminish. Whether in the rivalry with China or the predominance of Israeli interests in Middle East policy, for example, it is hard to imagine Biden taking a big step backward. Many Europeans want to believe that a victory by Obama’s former vice president will signal a return to the good old days of transatlantic consultation and multilateralism. In appearance, perhaps. But only in appearance, for the continents started drifting apart with the emergence of the post-Soviet world, i.e. more or less at the beginning of the new century. This drift is explained by objective factors, mainly the rise of China and the decline of Russia. The personality of successive presidents can only speed up or slow down the trend. This detail, however, is not an insignificant one. To reach his domestic policy ends, Trump has unflinchingly flouted all the conventions of foreign policy. Copycats have followed his lead, including Boris Johnson in Great Britain. From the perspective of the world’s stability as a whole, scorn for international law and institutions is worse than a crime. It is an offence against the world, and therefore also, it seems to me, against the United States. From this point of view, anyone other than Trump could perhaps soothe the wounds but not change the course of things. That is why some people on this side of the Atlantic hope the billionaire is re-elected. In their view, only such a jolt could bolster the Europeans’ tentative movement towards sovereignty.

For my part, I reject such speculations. First, because Europeans are merely observers of the American political scene. They have no means to influence it. Second, and above all, in the name of realism: whatever happens, a minimum of Euro-American understanding is necessary if Western countries, and those of all continents to which they are linked by history and geography, are to flexibly face the challenge of the rise of illiberal powers. There is also the challenge of political Islamism, which is incompatible with Western values, and a fortiori the persistent threat of Islamist terrorism. This necessary Euro-American understanding presupposes, however, that the United States, with or without Trump, should stop treating Europeans as adversaries by brutally imposing its own choices on them, in particular through sanctions. That said, it must be acknowledged that a second Trump term would hardly look different from the first one. If he prevails, the European Union would have no choice but to seek ways of escaping from Uncle Sam’s clutches without falling into those of China. The trickiest point is that at this stage there is nothing to suggest that a newly democratic America would not also seek to impose its will on Europeans, albeit in a slightly more gentle way.

To round out these pre-electoral comments, let us take a further step back with a more sociological look at today’s world. In the first place, the rejection of any notion of authority in general can be observed. The collapse of traditional forms of Christianity in the Western world, stunningly quick on the scale of history, is especially spectacular in this regard. This is globally true of Catholicism but also of Protestantism, with evangelical churches benefitting the most. The last point is striking in the United States, where what is left of Protestant culture, so important to the identity of the world’s leading power, has been transfigured into communitarian sects as unrealistic and intolerant as they are cut off from their roots. By analogy, how can a parallel not be drawn with communist ideology, that travesty of Christianity where God was replaced by “the people” and the Church by the Party? In Eastern Europe, the Orthodox churches are still holding their own. In the near future, it is perhaps in the United States that the loss of identity will be most striking, despite attempts to hide it. Ultimately, doesn’t the Trump phenomenon reflect the anxiety of that half of the population that genuinely fears that American values are disappearing? The fear of losing identity is not only seen in the United States. It has been visible in France for a long time. In fact, outside of Orthodoxy in Russia, if there is a monotheistic faith that for a half-century has ceaselessly bolstered its positions, both religious and political, it is Islam. And, since decolonization in the broad sense of the term, political Islam has had a tendency to degenerate into the worst forms of obscurantism.

After, or rather alongside religion, I would mention social media and the libertarian aura that still surrounds them. It has taken a long time to recognize that whole segments of public opinion throughout the world are influenced by a steady drumbeat of messages or unverified ”news”. The issues facing contemporary societies are extremely complex. And ethical judgements about them are never easy to make. They can only be addressed by looking at every side; no perfect synthesis is possible. When there is no longer any recognized authority, manipulators and cynics have a free hand to spread “alternative facts” and justify their crimes. technology is a formidable tool at their disposal. As time goes by, the need for Internet legislation will undoubtedly become increasingly felt. But before a new legal system emerges, how many tragedies will have unfolded and what effects will they have had?

For the record, let us mention without comment the explosive rise of inequality during the time of “happy globalization”, the over-exploitation of nature and the increasingly tangible manifestations of climate change. These facts alone would suffice to explain the return of quasi-revolutionary forms of socialism (or their appearance, in the case of the United States), which are a far cry from social democracy.

Lastly, there is the interminable COVID 19 crisis. It forces us to reconsider global governance in terms of health just when the trend—exacerbated by the pandemic—is towards de-globalization and the weakening of multilateralism. This weakening is aggravated by the suspicion, at least in Western opinion, that governments are too incompetent to carry out coherent and effective public policies.

In conclusion, I would add that authoritarian or totalitarian regimes are not immune to revolutions, partly for the same reasons. No country nowadays can be completely impervious to the gaze of others. The seemingly strongest regimes can be swept away in the blink of an eye. Imbalance is a global phenomenon. The best that can be expected from the next president of the United States is a little more wisdom. Wisdom and firmness are not mutually exclusive. That would already be a big step forward for the international system as a whole.

See you after the 3rd of November.

Thierry de Montbrial

Founder and Chairman of the WPC

Founder and Executive Chairman of Ifri

Franciscus Verellen et Jean-Pierre Cabestan, experts sur la Chine

4 Instituts Pour Mieux Comprendre La Chine D’Aujourd’hui

Forbes – 16.11.2020

Par Philippe Branche

“Quand on s’intéresse à la Chine : il est important de connaitre la pensée chinoise : d’Anne Cheng à Jacques Gernet en passant par Léon Vandermeersch”, explique le professeur Jean-Pierre Cabestan. A l’heure où le futur des relations diplomatiques avec la Chine est plus que jamais incertain avec l’élection de Joe Biden, le travail des sinologues est d’autant plus important. Peu connus du grand public, la France compte pourtant de nombreux instituts qui fournissent une intelligence de terrain pour les décideurs politiques et économiques. Retour pour Forbes France sur les différentes sources d’information pour comprendre la Chine d’hier et d’aujourd’hui.

Comprendre le passé de la Chine avec Franciscus Verellen – Ancien Directeur de L’École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), membre de l’Institut.

L’École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO). Une institution qui a donné ses lettres de noblesse à la sinologie française. Sa mission scientifique vise l’étude des civilisations classiques d’Asie par le prisme des sciences humaines et sociales. Depuis sa création en 1898, l’École a connu une croissance constante avec un total de 18 centres et antennes en Asie : de Pondichéry, à la Thaïlande, en passant par Tokyo ou encore Hong Kong, et même un chantier archéologique en Corée du Nord.

L’EFEO n’aurait pas pu connaitre un tel essor sans les compétences apportées par ses enseignants-chercheurs. Franciscus Verellen, ancien directeur de l’École de 2004 à 2014 qui est aujourd’hui responsable du centre de Hong Kong, décrit l’École comme un exemple reconnu au plan international de « l’importance de la connaissance directe et acquise sur le terrain qui reste, encore aujourd’hui, une spécificité de la sinologie française ». Les implantations de l’EFEO sont considérées par les décideurs politiques et économiques comme une ressource fiable sur la Chine comme sur l’Asie.

Les travaux de Franciscus Verellen s’inscrivent dans la tradition d’excellence de la sinologie française. Son ouvrage « Imperiled Destinies : the Daoist Quest for Deliverance in Medieval China » retrace sur huit siècles l’ouverture du taoïsme à différentes influences et l’essor de la religion chinoise par excellence. Un livre passionnant pour comprendre l’évolution du taoïsme et ses liens complexes avec le bouddhisme et le confucianisme. L’expertise de Franciscus Verellen lui permet aussi d’avoir une compréhension subtile des enjeux religieux actuels en Chine. Lors de son intervention à la World Policy Conference créée par Thierry de Montbrial, le sinologue a mis l’accent sur la réponse politique au fait religieux dans l’Empire du Milieu. Selon lui, la Chine est un « État fondamentalement religieux » et ce renouveau spirituel a été provoqué par « la question des valeurs ». Depuis février 2018 le Front uni du parti communiste chinois régule et « sinicise » les cinq religions reconnues, taoïsme, bouddhisme, islam, catholicisme et protestantisme. Franciscus Verellen fait ainsi partie des sinologues dont le regard d’historien est précieux pour mettre en perspective des enjeux contemporains.

MERICS et l’Insitut Ricci – deux instituts internationaux pour l’actualité chinoise

La France n’est pas le seul pays européen à vouloir mieux comprendre la Chine contemporaine ; l’Allemagne s’y intéresse également. En 2013 fut établi le Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), un think tank dédié uniquement à l’étude de la Chine. Les experts du MERICS se définissent d’abord comme “ouverts à de nouvelles perspectives sur la Chine et à de nouvelles propositions destinées à façonner les relations avec ce pays”. Leur dernier podcast, publié le 10 Novembre, ouvre des perspectives pour mieux cerner les enjeux d’actualité : “ US-Chine : les relations après les élections ”, un échange pour appréhender l’agenda chinois de Joe Biden. Ce think tank s’avère d’autant plus important que la Chine affiche malgré la pandémie mondiale un objectif de croissance annuelle du PIB de 5% pour les cinq prochaines années selon l’agence Reuters. De même, un autre institut plus ancien a pour objectif d’analyser les échanges culturels sino-occidentaux: l’Institut Ricci, dont le nom vient du premier prêtre Italien Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) à inaugurer l’inculturation du christianisme en Chine. Contrairement au MERICS qui se consacre principalement aux enjeux géopolitiques, ce dernier se consacre avant tout à l’étude de la civilisation chinoise et au dialogue interreligieux. Une conférence universitaire par Sophie Boisseau du Rocher (IFRI) devrait se tenir le 20 février 2021 prochain à Paris avec comme thème « Les Nouvelles Routes de la Soie, vues de l’Asie». Autant d’instituts donc pour mieux comprendre la Chine contemporaine d’un point de vue géopolitique et culturel.

Comprendre le présent du monde chinois avec Jean-Pierre Cabestan, ancien directeur du Centre d’études français sur la Chine contemporaine (CEFC)

Jean-Pierre Cabestan est directeur de recherche au CNRS et professeur à l’Université baptiste de Hong Kong. Il a été directeur du CEFC de 1998 à 2003 et s’intéresse tout particulièrement aux phénomènes politique en Chine populaire, à Hong Kong comme à Taiwan. Dans son ouvrage, ‘Chine-Taiwan, la guerre est-elle concevable?’, Jean-Pierre Cabestan d’une part analyse la menace chinoise et la capacité militaire, politique et économique de Taipei à résister. D’autre part, il évalue les risques de guerre et considère les différents scénarios possibles, avec ou sans implication américaine. Pour des sujets aussi sensibles et complexes, les experts comme Jean-Pierre Cabestan sont indispensables pour appréhender en profondeur cette zone de tension.

“En analysant l’histoire de la sinologie française, l’un des premiers pionniers de la recherche locale en Chine fut le général Jacques Guillermaz (1911-1998). Le général devient un observateur attentif des événements politiques de la Chine avec l’idée de l’étudier sur le terrain, une notion que de nombreux sinologues suivent encore aujourd’hui” explique Jean-Pierre Cabestan. “Le général a été l’un des fondateurs du Centre de recherche et de documentation sur la Chine contemporaine, qui fait maintenant partie de l’EHESS.” Dans son ouvrage Demain la Chine : démocratie ou dictature ? (publié en français et en anglais), Jean-Pierre Cabestan estime que le régime politique mis en place par Mao Zedong reste solide et doté d’une certaine capacité d’adaptation. Mais l’ancien directeur du CEFC pense qu’à plus long terme, du fait de la modernisation et la mondialisation de l’économie comme de la société chinoises, la question de la démocratie se posera, comme partout ailleurs.

Jean-Pierre Cabestan à la World Policy Conference ©

L’EFEO, le MERICS, l’Institut Ricci et le CEFC. Quatre instituts pour mieux apprécier la pluralité du monde contemporain chinois. Sans Franciscus Verellen ou Jean-Pierre Cabestan, il nous serait de plus en plus difficile d’appréhender le présent chinois. Par le biais d’un travail de recherches de terrain, nous comprenons qu’il y a non pas une mais différentes manières d’être chinois. “Ceux qui souhaitent bien connaître la Chine doivent se garder de prendre une partie pour le tout “ recommande finalement le Président chinois Xi Jinping.

Rozlyn Engel: Carnegie report on the U.S. foreign policy

Making U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Co-editors:

Salman Ahmed, Rozlyn Engel, Wendy Cutler, Douglas Lute, Daniel M. Price, David Gordon, Jennifer Harris, Christopher Smart, Jake Sullivan, Ashley J. Tellis, Tom Wyler

Summary

If there ever was a truism among the U.S. foreign policy community—across parties, administrations, and ideologies—it is that the United States must be strong at home to be strong abroad. Hawks and doves and isolationists and neoconservatives alike all agree that a critical pillar of U.S. power lies in its middle class— its dynamism, its productivity, its political and economic participation, and, most importantly, its magnetic promise of progress and possibility to the rest of the world.

And yet, after three decades of U.S. primacy on the world stage, America’s middle class finds itself in a precarious state. The economic challenges presented by globalization, technological change, financial imbalances, and fiscal strains have gone largely unmet. And that was before the novel coronavirus plunged the country into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, exposed and exacerbated deep inequities across American society, led long-simmering tensions over racial injustice to boil over, and launched a level of societal unrest that the United States has not seen since the height of the civil rights movement.

If the United States stands any chance of renewal at home, it must conceive of its role in the world differently. That too has become a point of rhetorical consensus across the political spectrum. But what will it actually take to fashion a foreign policy that supports the aspirations of a middle class in crisis? The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace established a Task Force on U.S. Foreign Policy for the Middle Class to answer that question. This report represents the conclusion of two years of work, hundreds of interviews, and three in-depth analyses of distinct state economies across America’s heartland (Colorado, Nebraska, and Ohio). It proposes to better integrate U.S. foreign policy into a national policy agenda aimed at strengthening the middle class and enhancing economic and social mobility. Five broad recommendations bear highlighting up front.

First, broaden the debate beyond trade. Manufacturing has long provided one of the best pathways to the middle class for those without a college degree, and it anchors local economies across the country, especially in the industrial Midwest. It makes sense, therefore, that so much of the debate about the revival of America’s middle class is centered around the effects of trade policy on manufacturing workers. But while millions of manufacturing jobs have been lost in the United States, other economic forces beyond global trade have also played a major role in the decline. In this sense, debates about “trade” are often a proxy for anxieties about the breakdown of a social contract—among business, government, and labor—to help communities, small businesses, and workers adjust to an interdependent global economy whose trajectory is increasingly shaped by large multinational corporations and labor-saving technologies.

Moreover, the majority of American households today sustain a middle-class standard of living through work in areas outside manufacturing, especially in the service sectors where the United States has competitive advantages. Many of these Americans generally support the trade policies of past decades that have largely served them well. In a February 2020 Gallup poll, 79 percent of Americans agreed that international trade represents an opportunity for economic growth.1 Many of these Americans are less concerned with overhauling past trade policies and are more preoccupied with how military interventions and changes in the United States’ global commitments, among other aspects of foreign policy, might affect their security and economic well-being.

Middle-class Americans are not a monolithic group. Their interests diverge. Different aspects of foreign policy impact them differently, including across gender, racial, ethnic, and geographic lines. Getting trade policy right is hugely important for American households but it is not a cure-all for the United States’ ailing middle class and represents only one element of a broader set of middleclass concerns about U.S. foreign policy.

Second, tackle the distributional effects of foreign economic policy. Globalization has disproportionately benefited the nation’s top earners and multinational companies and aggravated growing economic inequality at home. It has not spurred broad-based increases in real wages among U.S. workers. It has not driven a wave of public and private investments to enhance U.S. productivity generally and make more American workers and small businesses globally competitive. And while it has brought down the prices of certain highly tradable goods, it has done little to alleviate the growing pressure on American middle-class families from the rising costs of healthcare, housing, education, and childcare. Making globalization work for the American middle class requires substantial investment in communities across the United States and a comprehensive plan that helps industries and regions adjust to economic disruptions.

In particular, foreign economic policy will need to:

• prioritize international policies that will stimulate job creation and allow incomes to recover; • revamp the U.S. international trade agenda and ensure it is paired with a domestic policy agenda to support more inclusive economic growth;

• modernize U.S. and international trade enforcement tools and mechanisms to better combat unfair foreign trade practices that are especially harmful to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and workers;

• pursue other international agreements that close regulatory and governance gaps across countries to improve burden-sharing and help address equity concerns; and

• craft a National Competitiveness Strategy that includes efforts to make U.S. SMEs and workers more competitive in the global economy and enhances the ability of communities to attract job-creating business investment.

Third, break the domestic/foreign policy silos. For decades, U.S. foreign policy has operated in a relatively isolated sphere. National security strategists and foreign policy planners have articulated national interests and set the direction of U.S. policy largely through the prism of security and geopolitical competition. That remains a critical perspective, especially at a time when geopolitical competition with China, Russia, and other regional powers is on the rise. But with so many Americans now struggling to sustain a middle-class standard of living, threats to the nation’s long-term prosperity and to middle-class security demand a wider prism—informed by a deeper understanding of domestic economic and social issues and their complex interaction with foreign policy decisions. That is not an easy shift to make. It will take better interagency coordination, interdisciplinary expertise, and some policy imagination. It will also require the contributions of a new generation of foreign policy professionals who break free of the mold cast during the Cold War and its immediate aftermath.

Fourth, banish stale organizing principles for U.S. foreign policy. National security strategists and foreign policy planners in Washington, DC, crave neat organizing principles for U.S. strategy. But there is no evidence America’s middle class will rally behind efforts aimed at restoring U.S. primacy in a unipolar world, escalating a new Cold War with China, or waging a cosmic struggle between the world’s democracies and authoritarian governments. In fact, these are all surefire recipes for further widening the disconnect between the foreign policy community and the vast majority of Americans beyond Washington, who are more concerned with proximate threats to their physical and economic security.

A foreign policy agenda that would resonate more with middle-class households and, in fact, advance their well-being, should:

• reinvigorate relations with close allies to build an agile and cohesive network that can effectively address the full range of diplomatic, economic, and security challenges—from pandemics and cyber attacks to unsecure weapons of mass destruction and climate change—that could imperil middle-class security and prosperity;

• manage strategic competition with China to mitigate the risk of destabilizing conflict and counter its efforts toward economic and technological hegemony;

• reduce the threat of a digital crisis and promote an open and healthy digital ecosystem;

• boost strategic warning systems and intelligence support to better head off costly shocks and build up protective systems at home;

• shift some defense spending toward research and development (R&D) and technological workforce development to protect the U.S. innovative edge and enhance long-term readiness;

• strengthen economic adjustment programs to improve the ability of middleclass communities to adjust to inevitable changes in the pattern of economic activity; and

• safeguard critical supply chains to bolster economic security.

This may seem like a somewhat less ambitious foreign policy agenda than might be expected from a task force comprised of foreign policy professionals who served in Democratic and Republican administrations from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama. And to a large extent it is. That is the point. The United States cannot renew America’s middle class unless it corrects for the overextension that too often has defined U.S. foreign policy in the post–Cold War era. It is equally evident that retrenchment or the abdication of a values-based approach is not what America’s middle class wants—or needs.

Middle-class Americans have no illusion that their fate can be walled off from the fate of the world. They embrace the sense of enlightened self-interest that has motivated U.S. foreign policy over the past seven decades and want the United States to serve as a positive and constructive force around the world. They appreciate that U.S. foreign assistance cannot simply be about short-term transactional benefits for the United States but must serve a wider purpose. They understand that repressive regimes make the world less safe and less free, and that it is in the United States’ self-interest to stand up for human rights. All this requires a larger international affairs budget to retool American diplomacy and development for the twenty-first century.

Middle-class Americans interviewed also understand that the United States must sustain a strong national defense and that, moreover, it is in their economic interests. Defense spending and the defense industrial base are—and will remain for some time—the lifeblood for many middle-class communities across the country. That is why drastic cuts in the defense budget in the near term would be unwise. Instead of slashing the defense budget, a more prudent course would be to reduce defense spending gradually and predictably over the longer term, while shifting some resources toward a broader conception of national defense—to include workforce development, cyber security, R&D to enhance U.S. economic and technological competitiveness in strategic industries, pandemic preparedness, and the resilience of defense supply chains.

At the same time, middle-class Americans are concerned about the cost of U.S. interventions and the potential for political overreach. They want the country to exercise its power judiciously and to selectively seek out the best opportunities for effecting positive change. But to credibly assert global leadership, the United States must redress democratic deficits and social, racial, and economic injustice at home while seeking to reclaim the moral high ground abroad. The United States must get its own house in order.

Fifth, build a new political consensus around a foreign policy that works better for America’s middle class. None of the current major foreign policy approaches hold the key to American middle-class renewal—be it post–Cold War liberal internationalism, President Donald Trump’s America First, or progressives’ elevation of economic and social justice and climate change and the potential downsizing of U.S. defense spending. This may partly explain why no single view commands broad-based bipartisan support. In fact, despite the variation in middle-class economic and political interests, their foreign policy preferences point the way toward a potential new foreign policy consensus that is not yet reflected in today’s highly polarized political class.

A Gallup poll from February 2019 showed that 69 percent of Americans thought the United States should take a major or leading role in world affairs, a figure that has been relatively stable for a decade. There is simply very little public support for Trump’s revolution in U.S. foreign policy and its call to turn back the clock on globalization and international trade, constrain legal immigration, gut foreign aid, abandon U.S. allies, or abdicate U.S. leadership on the global stage. But that should not be overinterpreted as support for the restoration of the foreign policy consensus that guided previous Republican and Democratic administrations. That set of policies left too many American communities vulnerable to economic dislocation and overreached in trying to effect broad societal change within other countries. America’s middle class wants a new path forward.

A foreign policy that works better for the middle class would preserve the benefits of business dynamism and trade openness—which does not feature prominently enough in the progressive agenda—while massively increasing public investment to enhance U.S. competitiveness, resilience, and equitable economic growth. It would sustain U.S. leadership in the world, but harness it toward less ambitious ends, eschewing regime change and the transformation of other nations through military interventions. And it would recognize that a foreign policy that works for the middle class has to be connected to a domestic policy that works for the middle class.

Taken collectively, the task force’s recommendations provide a blueprint for rebuilding trust. So much of what is required to make U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class will not be visible to, or verifiable by, most Americans at the local level. And in many instances, it will require working through difficult trade-offs, where the interests of industries, workers, or communities do not align. The American people need to be able to trust that U.S. foreign policy professionals are managing this tremendous responsibility as best they can, with the interests of the middle class and those striving to enter it at the forefront of their consideration.

U.S. foreign policy professionals will also need to regain the trust of U.S. allies and partners, which no longer have confidence that the deals struck with one U.S. administration will survive the transition to the next or that basic alliance structures that have endured for decades are still a given. As a result, they are increasingly hedging their bets, trying to stay in the United States’ good graces while also keeping their options with China and other U.S. rivals open.

Restoring predictability and consistency in U.S. foreign policy requires building broad-based political support for it. And the best and perhaps only viable path right now to rebuilding such support lies in making U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class. The ideas in this report represent a starting point for discussion—one that will hopefully lead to healthy debate and bring many more innovative and actionable ideas to the table.

This publication can be downloaded at no cost at https://carnegieendowment.org/specialprojects/usforeignpolicyforthemiddleclass/.

Antoine Flahaut : Covid-19, peut-on continuer à tracer tous les cas contacts?

16.10.2020 – Heidi News

par Kylian Marcos

Les concepteurs de SwissCovid, application de traçage de contacts à l’échelle nationale, ont annoncé travailler sur une autre application destinée aux évènements privés. Dans plusieurs cantons, le traçage numérique des cas contacts est de rigueur, plusieurs applications se disputant le marché. Malgré cela, les services de santé publique sont proches de la rupture dans certains cantons, comme Genève. Se pose la question de la stratégie de traçage à adopter face à l’essor de nouveaux cas Covid-19.

Changer de focale. Le 15 octobre, dans son rapport quotidien, l’OFSP annonçait 2613 nouveaux cas en Suisse. A chaque fois, des personnes en contact sont placées en quarantaine. Ils sont actuellement plus de 11’000, selon l’OFSP, contre 6000 au début du mois. Pour le Pr Antoine Flahault, épidémiologiste et directeur de l’institut de santé globale de l’université de Genève, un changement de stratégie est nécessaire: […]

Antoine Flahaut est Directeur de l’Institut de Santé Publique à l’Université de Genève, et ancien directeur et fondateur de l’EHESP.

Laurent Fabius : La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique

16.10.2020 – Radio Classique

Antoine Mouly

La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique au regard de la gravité des phénomènes, selon Laurent Fabius

Laurent Fabius, président du Conseil constitutionnel était ce matin l’invité de Bernard Poirette. L’ancien président de la COP 21, à l’occasion de la sortie de son livre « Rouge Carbone » aux éditions de l’Observatoire, est revenu sur le changement climatique. Il en a notamment souligné le danger, affirmant que ses conséquences étaient plus graves que celle de la Covid.

L’élection américaine sera décisive dans la lutte contre le changement climatique

Interrogé par Bernard Poirette sur les perquisitions chez Olivier Véran, Agnès Buzyn, Edouard Philippe et Jérôme Salomon dans le cadre de la gestion de la crise sanitaire, Laurent Fabius a expliqué que cette situation lui a « évidemment rappelé son parcours » et l’affaire du sang contaminé. Pour l’ancien premier ministre, c’est « une évidence que les politiques doivent être transparents ». Il estime par ailleurs qu’ « il ne faut pas de politisation de la justice ni de judiciarisation de la politique ». Il est également revenu sur la formule de Georgina Dufoix « responsable mais pas coupable » qui est selon lui une « formule malheureuse » interprétée par l’opinion, à tort, comme une formule exprimant que les politiques se défilent devant leurs responsabilités.

Ancien président de la COP 21, Laurent Fabius est revenu sur ce qu’il restait de l’accord de Paris. Pour lui, cet accord restera comme « le premier accord mondial signé par tous les pays du monde pour enrayer le changement climatique ». Il a expliqué que ce résultat a été le fait de trois piliers : « le scientifique, la société civile et le politique ». Estimant que les deux premiers piliers ont continué à travailler dans le bon sens, il a pointé du doigt le manque dans la sphère politique et l’inaction de certains gouvernements : « l’accord reste mais il faut que la volonté politique soit mise en œuvre ». Sur ce point, l’ancien premier ministre est optimiste et a expliqué au micro de Bernard Poirette quels sont ses trois espoirs. Pour lui, le premier espoir réside en l’Europe, qui a une politique qui « va dans le bon sens ». Ensuite, il estime que la Chine représente un espoir avec les récentes annonces de son président Xi Jinping : « le président chinois a annoncé vouloir la neutralité carbone en 2060 ». Mais pour le président du Conseil constitutionnel, la grande question concerne l’élection américaine qui se tiendra dans deux semaines : « Si Donald Trump est élu, ce sera la catastrophe, alors que si c’est Joe Biden, il réintègrera l’accord de Paris et fera pression pour le respecter ».

« La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique »

Laurent Fabius a expliqué ce qu’il appelle le « giga paradoxe ». Selon lui, au regard de la gravité des phénomènes, « la Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique ». Il a en effet rappelé que le changement climatique cause plus de morts et a des conséquences à long terme plus grandes. Pour lui le grand effort à faire est « de faire prendre conscience que ce problème est tout aussi important que la Covid » et que nous devons « mobiliser toutes nos forces ». Un changement d’esprit doit s’opérer.

Selon l’actuel président du Conseil constitutionnel, « on ne peut pas se résigner » face à cette situation. Il a par ailleurs expliqué que le changement climatique ne sera pas un problème pour nos petits-enfants mais pour nous et que les « dégâts actuels sont déjà épouvantables ». Evoquant le recul des gaz à effet de serre pendant le confinement, il regrette que ces émissions « soient en train de repartir avec l’activité économique ». Il a affirmé la nécessité de « relances vertes et non pas brunes », des relances brunes qui risqueraient d’accroître encore plus les émissions de CO2 dans l’atmosphère. Laurent Fabius estime qu’il est indispensable d’ « intégrer la préoccupation environnementale à la relance économique ».

Enfin, Bernard Poirette l’a interrogé sur sa vision du futur. Laurent Fabius s’est dit « n’être ni optimiste, ni pessimiste mais volontariste ». Il a rappelé l’importance de tenir les engagements pris mais a aussi mis en garde expliquant qu’il faut aller plus loin. Le président du Conseil constitutionnel a expliqué que « si les engagements de Paris étaient respectés, nous limiterions le réchauffement à 3 ou 4 degré, alors que l’objectif est de 2 ». Ainsi, la COP de Glasgow qui se tiendra l’année prochaine aura un rôle déterminant pour évaluer à nouveau les objectifs.

Hélène Rey : « Le changement climatique ne pourra être combattu en réduisant l’activité économique »

14 octobre 2020 – Le Monde

Hélène Rey

L’économiste Hélène Rey préconise, dans sa chronique, de neutraliser l’effet de la taxe carbone sur la politique monétaire de lutte contre la hausse des prix.

Chronique. Emboîtant le pas de la Réserve fédérale américaine, la Banque centrale européenne (BCE) a décidé de réexaminer en profondeur sa stratégie de politique monétaire. Les pays européens s’étant engagés à atteindre une économie neutre en carbone d’ici à 2050, la BCE doit désormais réfléchir à la manière dont son cadre de politique monétaire peut contribuer à cette transition.

Bien que le traité sur le fonctionnement de l’Union européenne fasse du maintien de la stabilité des prix l’objectif principal du Système européen des banques centrales (SEBC), le texte énonce également que « sans préjudice de [cet] objectif… le SEBC apporte son soutien aux politiques économiques générales dans l’Union, en vue de contribuer à la réalisation des objectifs de l’Union, tels que définis à l’article 3 du traité sur l’Union européenne ». Selon cet article, l’Union « œuvre pour (…) une économie sociale de marché hautement compétitive, qui tend au plein emploi et au progrès social, et un niveau élevé de protection et d’amélioration de la qualité de l’environnement ».

Le changement climatique ne pourra être combattu en réduisant purement et simplement l’activité économique : une refonte des systèmes de production existants sera absolument nécessaire. La seule manière d’atteindre l’objectif zéro émissions d’ici à 2050 consiste à transformer nos modes de production, de transport et de consommation.

Chocs d’offre

L’un des moyens les plus efficaces pour y parvenir – voire le seul – consiste à augmenter le prix du carbone tout en accélérant la cadence de l’innovation technologique. Cette approche entraînerait toutefois inévitablement d’importants chocs d’offre. Le coût des intrants, en particulier des énergies, deviendrait plus volatile à mesure de l’augmentation du prix du carbone et du remplacement progressif des combustibles fossiles par les énergies renouvelables. De même, les transports et l’agriculture seraient également soumis à d’importants changements, potentiellement perturbateurs dans les prix relatifs.

Quel que soit le cadre monétaire dont conviendront les banques centrales, ce cadre devra pouvoir s’adapter aux changements structurels majeurs ainsi qu’aux effets sur les prix relatifs engendrés par la décarbonation. Dans le cadre actuel, la BCE cible l’inflation de la zone euro à travers l’indice des prix à la consommation harmonisé (IPCH). Or cet indice inclut les prix de l’énergie, ce qui le rend inadapté au défi de la décarbonation. L’inflation des prix du carbone étant décidée par les dirigeants politiques de l’UE, la BCE ne saurait tenter de pousser d’autres prix à la baisse dans l’IPCH alors même que le prix de l’énergie augmente, ce qui créerait des distorsions encore plus importantes.

Lire la suite de l’article (réservée aux abonnés) sur le site du Monde.

Europe’s futile search for Franco-German leadership

16 Oct 2020 | Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI)

Josef Joffe

For decades, France and Germany have been known as Europe’s ruling ‘tandem’ or ‘couple’, even its ‘engine’. Together, they aimed to work to unify the continent. But, to pile up the metaphors, the French want to drive the jointly leased Euro-Porsche, while the Germans insist on rationing the petrol money. As a long list of crises—from Belarus to Nagorno-Karabakh—now shows, the two countries are not following the same road map.

That’s not surprising. As former German foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel has put it, France and Germany ‘view the world differently’ and thus have ‘distinct interests’. The truth is that Franco-German divergence is almost as old as the European Union.

That division bedevils the current French and German leaders—President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel—as much as it did their towering predecessors, Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, ever since the two of them linked hands across the Rhine 60 years ago. They were to turn ancient enemies into trusted friends. But states don’t marry. They obey interests, not each other.

When two powers are so closely matched, the issue always is, who leads, and who follows? The hyperactive Macron certainly wants to run Europe (as, truth be told, all of his predecessors in the Élysée Palace have sought to do). Meanwhile, the plodding Merkel keeps stressing German priorities.

The current divergence is also a matter of personalities. Temperamentally, Macron is the opposite of Merkel. Whereas Macron craves the limelight, Merkel, known at home as Mutti (mum), reads from a well-thumbed script about continuity and caution.

This is reflected in their foreign policies as well. Since he won the presidency in 2017, Macron has successively flirted with US President Donald Trump, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping, then turned away in disillusion from all three. France simply doesn’t play in their league. Merkel, by contrast, has kept her distance from Trump, Putin and Xi.

Macron has also pronounced the ‘brain death’ of NATO, echoing Trump’s description of the alliance as ‘obsolete’. But a German chancellor would be the last to turn off the lights at the alliance’s headquarters in Brussels. After all, NATO has guaranteed Germany’s security for 70 years—and at a steep discount.

The most recent Franco-German disagreements centre on the eastern Mediterranean, where Greece and Turkey—both NATO members—threatened to come to blows over gas exploration in contested waters. Macron was quick to side with Greece, dispatching warships and planes while promising arms. Last month, he hosted a summit in Corsica involving the leaders of six other Mediterranean EU member states to provide a counterweight against Turkey. Germany wasn’t there.

Merkel instead mumbles platitudes about a ‘multi-layered relationship’ with Turkey, which must be ‘carefully balanced’. German interests are clear: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is guarding the Turkish–Syrian border against an uncontrolled influx of Middle Eastern refugees who will head for Germany if given half a chance. Provoke him, and he can open the refugee spigot at will.

Then there’s the current flare-up between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Macron, Putin and Trump have urged the two countries to negotiate immediately, while Erdogan has sided with the Muslim Azerbaijanis against Christian Armenia. Germany, however, is merely ‘alarmed’, because Merkel can’t afford to alienate Erdogan.

After large parts of Beirut were levelled by a deadly explosion in August, Macron dashed off to Lebanon, pledging to organise an international donor conference without coordinating with Merkel. France, which controlled the Levant after World War I, wants to keep a foot in the door to maintain its regional influence; Germany has no strategic interests there and instinctively shies away from anything smacking of escalation. Different interests, different schemes.

Germany is also taking a hands-off approach to Libya, whose civil war has drawn in Russia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and France. The best Germany can do in the Middle East is to arrange yet another peace parley in Berlin, as is the German habit.

This is just a short list of Franco-German foreign policy differences in the past few months. But it confirms the pattern: France likes to jump in, while Germany prefers to hang back. Merkel recently proclaimed ‘the hour of Europe’ in an ‘aggressive world’. But if France and Germany won’t pull together, how could the other 25 EU members?

The irreducible reason is structural. Twenty-seven do not add up to one, whether on Russia or Belarus, where President Alexander Lukashenko is dead set on wiping out the democracy movement. When the 27 tried to hash out sanctions against Belarus, tiny Cyprus refused unless the rest agreed to penalise Turkey over illegally exploring for gas in the Mediterranean.

That could have been anticipated. Cyprus is practically a Russian economic colony, and Lukashenko is Putin’s client. After weeks of wrangling, Cyprus finally relented. The EU will now sanction 40 Belarusian officials—a punishment that gives Lukashenko no reason to pack his bags.

The EU is the world’s second-largest economic power, ahead of China, and on paper has as many troops as the United States. But riches alone do not make a strategic actor. If they did, Switzerland would be a great power.

Of course, no European leader will ever fail to appeal to Europe’s common destiny. But in the EU’s case, ‘unity’ is often the opposite of ‘agency’, the capacity to act as a whole. A bloc of 27 states bound by a unanimity requirement on issues members consider essential will never be a strategic actor, because it will always be guided only by the lowest common denominator that all can accept.

Even if France and Germany ever do march in lockstep, the others will not fall into line, because they fear the duo’s domination. Unless and until they fuse into the United States of Europe, the EU’s member states will never leave vital strategic issues up to majority rule.

Read the original article on ASPI.

Joschka Fischer : Transatlantic Tragedy

Sept 28, 2020

By Joschka Fischer

BERLIN ― Between the intensifying Sino-American drama and the persistent COVID-19 crisis, the world is undeniably undergoing fundamental, historic change. Seemingly immutable structures built up over many decades are suddenly exhibiting a high degree of malleability, or simply disappearing altogether.

In the ancient past, today’s unprecedented developments would have put people on guard for signs of a coming apocalypse. In addition to the pandemic and geopolitical tensions, the world is also confronting the climate crisis, the balkanization of the global economy, and the far-reaching technological disruptions brought on by digitization and artificial intelligence.

Gone are the days when the West ― led by the United States, with the support of its European and other allies ― enjoyed unchallenged political, military, economic, and technological primacy.

Thirty years after the end of the Cold War ― when Germany was reunified and the U.S. emerged as the world’s sole superpower ― the case for Western leadership is no longer credible, and East Asia, with an increasingly authoritarian and nationalistic China at the helm, is moving swiftly to replace it.

But it wasn’t the escalating rivalry with China that weakened the West. Rather, the West’s decline has been driven almost entirely by internal developments on both sides of the Atlantic, particularly ― though not exclusively ― within the Anglo-Saxon world.

The United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum and U.S. President Donald Trump’s election in 2016 marked a definitive break in the transatlantic commitment to liberal values and a global rules-based order, heralding the revival of a narrow-minded fixation on national sovereignty that has no future.

The transatlantic West, a concept embodied in the establishment of NATO after World War II, was the result of the military triumph of the U.S. and U.K. in the Pacific and European theaters. It was these two countries’ leaders who created the post-war order and its principal institutions, from the United Nations and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (the precursor to the World Trade Organization) to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

As such, the “liberal world order” ― and indeed “the West” generally ― was wholly an Anglo-Saxon initiative, one that victory in the Cold War further vindicated.

But in the ensuing decades, the Anglo-Saxon world’s powers have been exhausted, and many of its people have begun to long for a return to a mythical imperial golden age. The prospect of reclaiming past greatness has become a successful political slogan in both countries.

Between Trump’s “America First” doctrine to U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s effort to “take back control,” the common denominator is a yearning to relive idealized moments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In practice, these slogans amount to a self-defeating reversal. The founders of an international order that enshrines democracy, the rule of law, collective security, and universal values are now dismantling it from within, thereby undercutting their own power. And this Anglo-Saxon self-destruction has created a vacuum, leading not to a new order but to chaos.

Of course, Europeans ― starting with the Germans ― are in no position to sit back complacently or point the finger at the Anglo-Saxons. By free-riding on security matters and simply shrugging their shoulders at persistently high trade surpluses, they, too, bear responsibility for today’s nationalist resurgence.

If the West ― as an idea and as a political bloc ― is to survive, something will have to change. The U.S. and the European Union will each be weaker alone than as a united front. But Europeans now have no other choice but to transform the EU into a genuine power player in its own right.

A deep rift has opened up between continental Europeans ― who must hold on to the traditional Western construct ― and increasingly nationalistic Anglo-Saxons.

After all, Brexit is not really about pragmatic questions of trade; rather, it represents a fundamental break between two value systems. More to the point, what happens if Trump is re-elected in November?

The transatlantic West almost certainly would not survive the next four years, and NATO would probably face an existential crisis, even if Europeans increase their defense spending in response to U.S. demands. For Trump and his followers, the money isn’t really the issue. Their primary concern is with American supremacy and European fealty.

By contrast, if former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden is elected, the tone of transatlantic relations would certainly become friendlier. But there is no going back to the pre-Trump era. Even under a Biden administration, Europeans would not quickly forget the deep distrust that has been sown these past four years.

Whoever wins in November, the U.S. will have to deal with a Europe that puts much greater stock in its own sovereignty ― particularly on technological matters ― than it has in the past. The cozy interdependencies of the immediate post-Cold War years are long gone.

The relationship will have to be remodeled, and both sides will need to adjust. Europe will have to do much more to safeguard its own interests, and America would do well to understand that Europe’s interests may diverge from its own.

Joschka Fischer, Germany’s foreign minister and vice chancellor from 1998 to 2005, was a leader of the German Green Party for almost 20 years.

François Barrault : La 5G, un enjeu géopolitique ?

BMF Business | 29 septembre 2020

Ce mardi 29 septembre, François Barrault, président de l’IDATE DigiWorld, est revenu sur les enjeux de la 5G et a parlé de son top départ pour la vente aux enchères des fréquences, dans l’émission Good Morning Business présentée par Sandra Gandoin et Christophe Jakubyszyn.

Good Morning Business est à voir ou écouter du lundi au vendredi sur BFM Business. Dans “Good morning business”, Christophe Jakubyszyn, Sandra Gandoin et les journalistes de BFM Business (Nicolas Doze, Hedwige Chevrillon, Jean-Marc Daniel, Anthony Morel…) décryptent et analysent l’actualité économique, financière et internationale. Entrepreneurs, grands patrons, économistes et autres acteurs du monde du business… Ne ratez pas les interviews de la seule matinale économique de France, en télé et en radio.

Retrouvez l’article original et la vidéo de l’interview sur BFM Business.

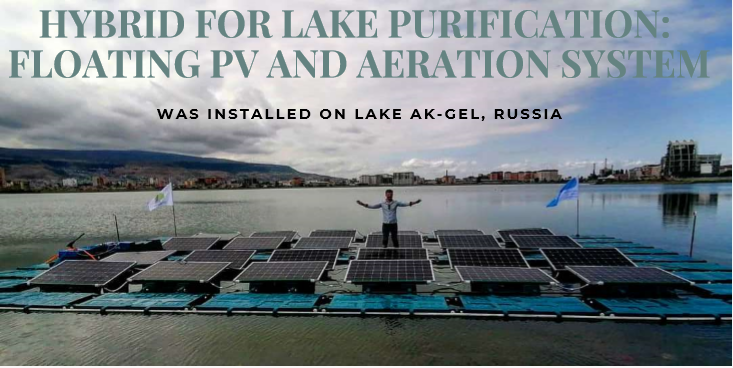

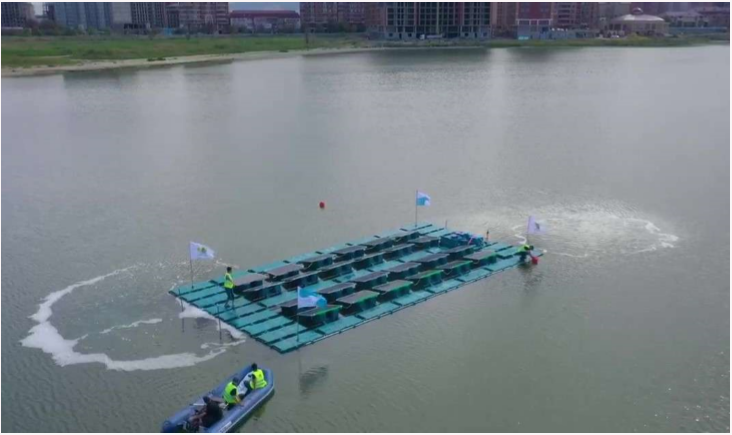

Polina Vasilenko: HelioRec installed the first in the world hybrid system for lake purification

HelioRec | September 2020, Issue 1

Fruitful cooperation between EcoEnergy and HelioRec

On 13th of September 2020 the first in the world hybrid system for lake

purification: floating PV and aeration system was installed on lake Ak

Gel. This lake is located in the center of Makhachkala (Dagestan

Republic, Russia) and it faces many serious ecological problems:

- Oxygen concentration is 3 times less than normal;

- Active algae growth;

- Water evaporation (area was reduced twice during the last 20 years).

Engineers from HelioRec, a Skolkovo innovation center resident, and EcoEnergy (project developers) invented the unique solution to solve these problems.

Floating power plant with the total area of 150 m2 that consist of:

- 24 floaters with 295W photovoltaic modules (Solar Systems);

- 36 footpaths;

- 4 batteries;

- 4 aerators which can help to bring needed amount of oxygen to revive the lake within 1 year.

In the process of developing the first project of its kind in the world,

engineers were required to apply fundamentally new solutions: aerators are powered by an autonomous solar generation with a 7 kW capacity based on a floating system, and “smart control technology” allows to control the power plant from a mobile phone. The system could survive the first storm (19th of September 2020) with wind speed more than 30 m/s. Based on the results of the first installation, HelioRec and Eco-Energy will decide about increasing size of the power plant and further project development.

Would like to build something innovative, let us know: savetheplanet@heliorec.com

See more of the project here.

Ana Palacio : The EU Merry-Go-Round

Project Syndicate | Sep 24, 2020

by Ana Palacio

EU leaders have tended to operate on the assumption that Europe is inevitable, and that Europeans are inescapably bound together in a community of fate. But many citizens don’t see it that way, and if they aren’t given a more convincing rationale for European integration, the only inevitability will be the EU’s demise.

MADRID – In her first State of the European Union address, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen offered a wide-ranging view of the current moment. She touted Europe’s recent achievements and identified its goals for the coming years. She dedicated significant attention to the European Green Deal and the Digital Agenda, and called for the completion of the banking union and capital-market integration. In normal times, it would have been a solid, if not particularly inspiring, performance. These are not normal times.

Yes, the policies and actions Von der Leyen described are important. But, at this point, no policy will fortify the EU’s foundations sufficiently. No grand-sounding program or budget increase will ensure its progress. No amount of common debt will guarantee its survival. To survive and thrive, Europe needs an overarching vision that captures the breadth of the challenges it faces, establishes a sense of common purpose among all citizens, and galvanizes popular support.

EU leaders have long peddled a hollow concept of European citizenship, one that emphasizes rights, rather than responsibilities and shared burdens. They have shown what the EU does, but not what the EU is for. And many refuse so much as to discuss the question. They believe the answer to be self-evident: Europe is inevitable, and Europeans are inescapably bound together in a community of fate.

But many citizens don’t see it that way. If they aren’t given a more convincing answer, the only inevitability will be the EU’s demise.

There have been glimmers of hope that EU leaders recognize the need to engage European citizens actively. For example, as part of the messy compromise that led to her confirmation as Commission president in 2019, Von der Leyen floated the idea of a Conference on the Future of Europe – a platform for engaging citizens in a wide-ranging debate on what the EU should look like and how to achieve it.

But the initiative has been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. And even if it is implemented, it will most likely go the way of other much-touted citizen-outreach efforts, such as the underwhelming European Citizens’ Consultations of 2018. Discussions will receive plenty of press, a report will be drawn up, and a communiqué released. Then another crisis will arise, and EU leaders will all but forget it. Its only lasting impact will be the resignation and even resentment felt by the citizens who participated.

The Conference on the Future of Europe was relegated to a single passing reference in von der Leyen’s address, as she discussed the post-pandemic organization of health competencies within the EU. Moreover, the European Council has already rejected the possibility of any treaty change stemming from the Conference. The more engaged citizens are with Europe, the less they will need their national governments to act as intermediaries. The same anxiety has fueled opposition to a European-level tax, which would make the EU directly accountable to citizens.

But if the initiative has no real stakes, it will attract no significant citizen buy-in. The same goes for the European project more broadly: if citizens feel no sense of ownership over the EU and no sense that their fates are tied to those of their fellow Europeans, they will never offer anything more than passive support. And passive support simply will not get the EU or its member states – to where they need to be.

It is preposterous that in 2020, 11 years after the eurozone crisis, the European Commission president is still calling to complete the banking union in her state of the union address. Her statement on migration – it is a “European challenge,” to which we can find a solution, “if we are all ready to make compromises” – was one that should have been made and agreed to in 2015, at the height of the migration crisis. Even her comment on Belarus rang hollow, given the EU’s failure to agree on sanctions against President Aleksandr Lukashenko’s regime. And round and round we go.

Bertrand Badré : “Il faut saisir ‘l’opportunité’ du Covid pour changer” le système économique

Europe 1 | 24 septembre 2020

Julien Ricotta

Bertrand Badré, un homme d’affaires réputé proche d’Emmanuel Macron, publie un livre pour appeler à repenser le modèle économique actuel. “Il faut saisir l’opportunité du Covid, entre guillemets, pour changer ce qui peut l’être”, a-t-il déclaré jeudi soir sur Europe 1.

INTERVIEWLe système économique actuel va-t-il survivre au coronavirus ? Fragilisée de toutes parts par la pandémie de coronavirus, l’économie mondiale continue de souffrir, de l’Europe aux États-Unis en passant par la Chine. Bertrand Badré, un homme d’affaires réputé proche d’Emmanuel Macron, plaide pour une refonte du système capitaliste dans un livre intitulé Voulons-nous (sérieusement) changer le monde ? – repenser le monde et la finance après le Covid-19. “Il faut saisir l’opportunité du Covid, entre guillemets, pour changer ce qui peut l’être. A partir du moment où l’on investit des milliards et des milliards, on doit les mettre dans la bonne direction”, a-t-il insisté jeudi soir sur Europe 1.

“On a gâché la crise précédente”

Le directeur de la société d’investissement Blue Like an Orange a pointé du doigt les failles du système actuel, héritées selon lui d’une mauvaise gestion de la précédente crise économique entre 2008 et 2011. “On a gâché la crise précédente, la crise financière dite des subprimes et de l’euro. A l’époque, on a colmaté les brèches mais on n’a pas repensé le système, qui a été rafistolé et qui a montré ses fragilités avec le Covid”, a constaté le financier.