July 3, 2018

Masood Ahmed, CGD

This note is adapted from a chapter that Masood Ahmed contributed to Pakistan at Seventy: A Handbook on Developments in Economics, Politics and Society (Europa Publications, forthcoming).

A brief history of Pakistan’s macroeconomic management

Over the past 50 years, Pakistan’s record on macroeconomic management has been mixed. In the face of a variety of internal and external shocks, the country has managed to avoid excessive macroeconomic instability in the form of hyperinflation or severe exchange rate volatility. While its internal and external public debt has grown as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), and is now approaching levels that warrant attention, Pakistan has so far managed this growth without resorting to sovereign defaults, which leave a long shadow on a country’s ability to access capital markets. Finally, Pakistan has also avoided the kind of large-scale banking crises that many other developing countries have experienced with lasting impact on credit availability and private sector development.

Alongside these positive features, however, Pakistan has demonstrated an almost unique proclivity to allow fiscal and balance of payments pressures to build up into a near-crisis situation every few years, which then must be dealt with through orthodox economic stabilization tools, often with the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In general, these stresses have been contained before they could become a full-blown economic crisis, but the cumulative cost of these periodic crisis-aversion programs has been to slow down economic and social development, resulting in the mediocre—and in some cases, poor—comparative development indicators that we see today. And, because each episode was addressed with short-term actions that stabilized the economy without adequate follow-through on structural reforms, the underlying weaknesses simply manifested themselves again with the next external shock or period of internal economic mismanagement. Moreover, this preoccupation with managing short-term macroeconomic vulnerabilities has limited the attention that top policymakers can devote to more fundamental issues of economic development and structural transformation.

The next crisis is now approaching. After successfully containing macroeconomic imbalances under an IMF-supported program during 2013–16, irresponsible fiscal expansion and a misguided attempt to maintain an increasingly overvalued exchange rate have led to a large and unsustainable balance of payments imbalance, a steep decline in foreign exchange reserves, and a sharp buildup of external debt, some of it on short maturities and expensive terms. Most economists agree that the post-election government will have no alternative but to approach the IMF yet again for another bailout with associated policy conditionality.

Against this background, this note examines three questions that economists both within and outside Pakistan are asking:

- Why does Pakistan have these repeated episodes of macroeconomic distress?

- Why have 18 IMF-supported programs failed to deal with this problem in a sustainable way?

- Is the potential availability of IMF financing itself an impediment to the policy changes that would reduce the economy’s vulnerability to crisis, and would it be better if the IMF did not provide support to Pakistan the next time there was a macro-crisis?

The causes of repeated macroeconomic distress

The principal factors leading to periodic episodes of macroeconomic stress are chronic and uncorrected structural weaknesses in Pakistan’s economy. While—as in most developing countries—there are many areas of economic management that can be improved in Pakistan, the two principal causes of macroeconomic problems have been the imbalance between public sector spending and income, and Pakistan’s underdeveloped export base, which makes the country highly vulnerable on the external sector.

Income and expenditure of the public sector

There has been a chronic imbalance between the income and expenditure of the public sector. This is not because Pakistan’s public budget is much larger, in relative terms, than that of other emerging markets. Rather, it is because the government’s income from taxes, fees, and other sources is strikingly low compared with other countries.

This is not to say that there is no waste in public spending, or that it could not be better allocated. There are well-documented studies that show how both current and capital spending by the federal and provincial governments and their associated bodies could be dramatically improved to get “more bang for the buck.” Similarly, the persistent losses made by some public sector enterprises,[1] and the even larger losses made in the energy sector,[2] provide additional scope for improving public finances. The case is all the more compelling given the comparatively low level of public spending on health and education, which explains, at least in part, why Pakistan lags woefully behind on social indicators of development. Finally, inadequate public investment in infrastructure constrains the potential for sustained high growth. There is, therefore, a clear need to rationalize and improve the effectiveness of public expenditure.

However, it is on the revenue side that Pakistan is among the weakest performing countries in the developing world. Despite 40 years of efforts to improve both tax policy and tax administration, the ratio of taxes to GDP remains stuck in the low teens, below the middle-income countries (MICs) average of around 18.5 percent.[3] In addition, the tax system is complicated, distorting, and not sufficiently progressive.

Two features of the tax structure are worth noting in particular: the high proportion of taxes collected through indirect taxes (60 percent of total tax revenue) and the small number of individuals who file income tax returns. Indirect taxes—essentially excise taxes, import duties, and fees of various sorts—are generally more regressive than direct taxes; in other words, their burden falls disproportionately on the poor and less well-off households. A further problem is that the second-best system of withholding and presumptive taxes has grown very complex, adding to the negative perceptions of the overall tax system. Attempts to introduce a VAT, a more efficient indirect tax, have failed in the face of political opposition.

The low number of income tax filers (just over one million out of an estimated working population of 116 million[4]), and the prevalent underreporting of income by those who do file, has important consequences. First, it limits total tax revenue for the government. Indeed, it is hard to envisage how the tax to GDP ratio could be increased by 50 percent (to reach the norm for developing countries) without a substantial increase in the number of filers in the tax net.

Second, tax avoidance or under payment undermines public confidence in the fairness of the tax system. The perception (and reality) that people who are known to have very high incomes pay little or no income tax fosters a sense that the system is rigged to protect the rich and powerful. The annual publication of tax payments by parliamentarians, demonstrating in many cases a clear disconnect between their declared tax payments and their visible standard of living, has been a great advance in transparency, but, so far, it has not altered the underlying pattern of behavior.

Those who claim to derive their income from agriculture (on which no income taxes are paid), and those engaged in trading or professional services who are either unregistered as taxpayers or pay small amounts in relation to their perceived incomes, are also often viewed as benefiting from an inequitable system. Property is mostly undervalued for tax purposes, so the revenue from this potentially important source is also very low by international comparison.

Tax avoidance is also found in the corporate sector. Of the 72,500 firms registered with the Security and Exchange Commission of Pakistan in 2016, less than half filed a tax return and half of the filers had a “zero return.”[5]

Many studies have considered the problems of tax policy and tax administration. On the policy side, the recommendations range from proposals to address specific anomalies or missed opportunities all the way to plans for a complete revamp, with a new simplified and efficient approach to setting up a tax system. Similarly, there are incremental as well as radical proposals to reform tax administration, which is generally seen as inefficient and plagued by corruption. There have also been a variety of projects over the years, many supported by international agencies with technical assistance and policy conditionality, to promote these recommendations.

Why have past programs failed to generate a substantial and lasting improvement in Pakistan’s tax outcomes? Many blame corruption and incompetence in the tax administration, and this is certainly part of the explanation. Others point to the large share of the informal sector in Pakistan’s economy, which makes it harder to track individual and small business incomes. Yet others will point to the fact that a large share of the working population would fall below any reasonable income threshold for paying taxes. Finally, there is the problem of lack of trust in the quality and integrity of government spending. Many observers point to the generous levels of private charity by people who pay little in taxes as demonstrating that people are willing to contribute to the larger social good if they are confident that the money will be put to good use. These observers maintain that lower levels of tax avoidance would naturally follow a demonstrated improvement in the coherence and effectiveness of government spending. All these points have some truth to them, but they also apply to other countries that have, nevertheless, succeeded in enrolling much larger numbers of their working population into the tax net.

The larger and more important explanation for Pakistan’s failure to improve its tax outcomes, in my view, is one of political economy. Pakistan simply lacks a powerful enough coalition of interests to raise more taxes and to push for real improvements in the quality of government spending. Normally, this would come from a combination of those in government who want to spend money without raising the deficit and private taxpayers who are increasingly resentful of the high tax rates they pay while their peers remain outside the tax net. While both groups exist in the country, they have not been able to come together and overcome the powerful interests on the other side.

In particular, governments have often backtracked on their efforts to widen the tax net when faced with opposition from their political constituencies or linked interests. As a result, in times of fiscal stress, it has proved easier to cut back on the already low level of public investment spending, with damaging—but lagged—consequences. Many donor agencies and international partners—including the World Bank, the IMF, and bilateral aid agencies—have tried to influence this process through a combination of carrots and sticks, but they too have not succeeded.

Until Pakistan can substantially raise tax revenue by broadening the base of direct taxpayers, it will remain constrained in its ability to expand the delivery of much-needed public services and infrastructure without building up unsustainable fiscal deficits. And without that extra infrastructure and improved human development, growth will remain elusive and the country’s place in an ever more competitive world economy will remain fragile. What events or forces will bring about the political consensus to overcome longstanding constraints in this regard remains a subject of discussion.

The external sector

The second source of macroeconomic vulnerability for Pakistan has been its external sector. Most successful emerging markets followed a strategy of promoting both the quantity and quality of their exports. Starting from low export levels comprised mainly of relatively unprocessed commodities or low value-added manufactures, these countries have dramatically expanded the volume, diversity, and sophistication of their exports. The most-often cited examples are China and the so-called East Asian tigers (Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia), but countries in other regions also provide good case studies.

In contrast, exports have remained a much smaller share of Pakistan’s economy since independence. And over the past three years, a combination of factors—security and energy supply problems, lower commodity prices, and an appreciating real exchange rate—have brought exports down to well below 10 percent of GDP. As shown in table 1, exports from Pakistan would have to more than triple from their current level to match the average for MICs. Pakistan’s exports have also been remarkably concentrated in a few low value-added products. Cotton and cotton products, rice, and leather still account for over 70 percent of the country’s exports, and the bulk of exports in each of these categories is in primary or little processed form. Service exports, which have been a rapidly growing source of high value-added export revenue in many countries, remain a small fraction of Pakistan’s exports.

Table 1. Exports of goods in 2017

| Country or Group |

USD billion |

% of GDP |

| Pakistan |

23.1 |

7.62 |

| Turkey |

166.1 |

19.56 |

| Malaysia |

188.0 |

59.76 |

| Thailand |

235.1 |

51.63 |

| India |

304.1 |

11.65 |

| Bangladesh |

35.30 |

13.51 |

| Middle-Income Countries Average |

76.65 |

24.47 |

Source: IMF Balance of Payments Statistics

Note: Data missing for numerous MICs. For a list of MICs, see footnote 3.

Given its low level of exports, Pakistan has relied in recent years on a large and growing volume of remittances and on official and private financing to cover its import bill. It is worth noting, however, that these international flows, especially private flows, can be volatile because they are subject to external and internal shocks. Pakistan has had a consistent rising trend of remittance flows for many years, but recent international economic developments suggest that this is unlikely to persist. Remittances from the Gulf countries, which have been a large and growing share of the total, are likely to plateau as these countries adjust their spending to the new lower price of oil. Pakistan will need to adjust to lower growth in remittances going forward.

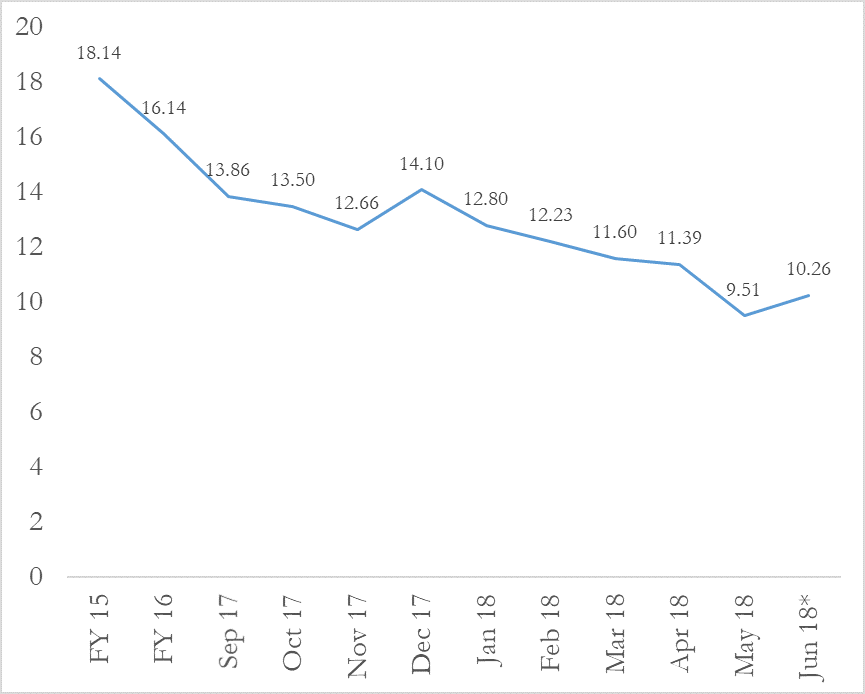

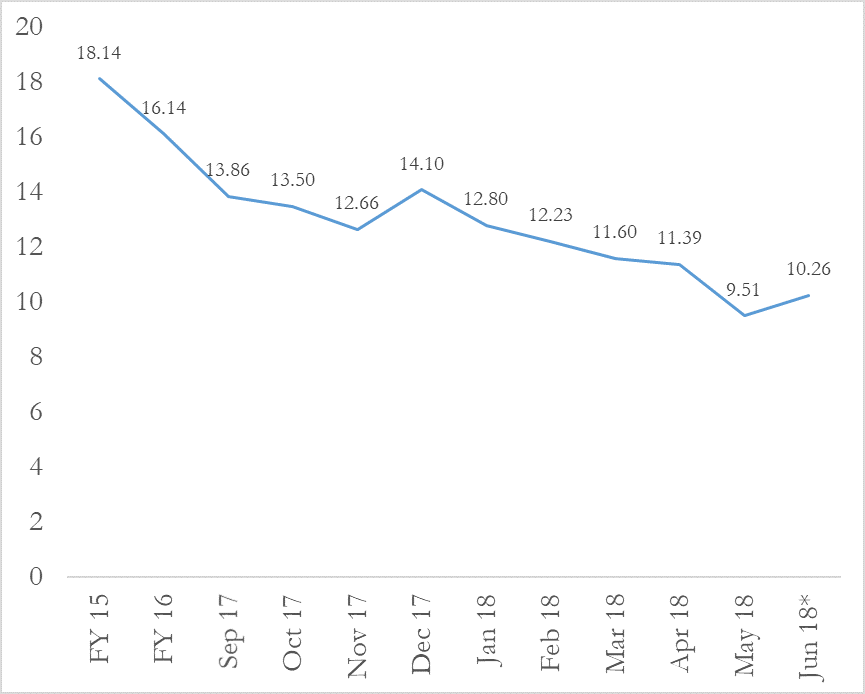

In good years, these international inflows have been sufficient not only to meet the demands for foreign exchange—even with an appreciating real exchange rate—but also to lead to an increase in the country’s foreign exchange reserves. However, when there was an external shock—such as the increase in oil prices in the years leading up to 2014—or when an excessively loose fiscal stance or a misguided exchange rate policy translated into an increased demand for foreign exchange, as has been the case more recently, these reserves were drawn down, sometimes to a level that threatened a macroeconomic crisis and led to recourse to the IMF (figure 1). At the time of writing, after a few years of being on a positive trajectory, these reserves were again on a downward trend and hovering around $10 billion, below the three months of imports mark that is used by many institutions as a minimum for certain kinds of financial operations.

Figure 1. Liquid foreign exchange reserves with the State Bank of Pakistan

USD billion, end period

Source: State Bank of Pakistan

*Second week of June

There are many factors that underpin Pakistan’s long-term export performance. Security problems, energy shortages, poor infrastructure, and other shortcomings in the business environment provide a good part of the explanation. Pakistan is 147th in the ranking of countries in the World Bank’s Doing Business report—an indication of its less-than-favorable business climate. A lack of investment in the export sector; or in updating technology and research and development that would raise the value added of exports; or in the educational system to generate enough trained technicians, workers, and managers are other reasons.

Also contributing to the small share of exports in Pakistan’s economy is the protected environment for the domestic market, which has made import substitution a profitable and less risky endeavor for many businesses. It is noteworthy that the largest corporations in Pakistan are either in manufacturing for the domestic market or in the service sector. A few rely on explicit or implicit protection in the form of import barriers or administered prices for inputs and outputs.

Finally, over the years a misguided adherence to an overvalued exchange rate has made it harder for Pakistani exporters to compete in international markets (while also resulting in the loss of a substantial share of foreign exchange reserves in an attempt to prevent necessary exchange rate depreciation). In contrast, some of the more successful emerging market exporters have seen the exchange rate as a tool to preserve their competitiveness and to build foreign exchange reserves to enhance their resilience and economic independence.

Behind these specific factors is the political economy of reforming the anti-export bias. Under the current regime, consumers have benefitted from cheaper imports and entrepreneurs have moved into producing for the domestic market with some degree of protection or in other non-tradeable activities. Exporters have voiced concerns about the exchange rate and other factors affecting their competitiveness, but they have sought government financial support rather than effectively lobbying for a more export-friendly regime.

Can Pakistan’s economy be made more export oriented? The entrepreneurial capacity and business acumen is certainly there. The performance of the small and medium enterprises sector in Sialkot is a striking example of success despite the weaknesses in the business environment and in infrastructure. However, to generalize this type of success requires a combination of public policy and supportive infrastructure investments. In this context, recent improvements in the security situation are welcome, as are investments to increase the capacity for electricity generation and—less so—distribution.

These efforts will need to be supplemented, however, by a much more fundamental revisiting of the public policy and business environment to better align incentives towards exporting. Exchange rate policy will need to prioritize economic fundamentals over seeing a “strong” exchange rate as a mark of national pride. Incremental schemes to provide limited subsidies or special incentives to exporters will only have a limited effect. If Pakistani policymakers truly want to quadruple the volume of exports, it will take nothing short of a national drive sustained over at least a decade. And it will require the political will to resist the calls of vested interests that gain from the current protectionism and anti-export bias.

Why have repeated IMF-supported reform programs failed to deal with the causes of macroeconomic vulnerability?

These two main structural weaknesses—fiscal imbalance and weak export performance—have been present for many decades, and their role in generating macroeconomic vulnerability is well understood. It is legitimate then to ask why they were not addressed under the numerous IMF-supported programs. Of course, the IMF is only one external agency engaged with Pakistan on economic policy questions. Still, the IMF’s focus on macroeconomic stability and its unique access to senior policymakers make the question more directly relevant to it. To be sure, many IMF-supported programs did attempt to address these structural issues, but, in the end, they were only partially successful. Why wasn’t a better and more sustainable improvement achieved despite repeated recourse to IMF financing and the associated policy conditionality?

The answer is that while IMF policy conditionality can reinforce what national governments are committed to doing, it cannot by itself achieve sustained policy change where there is no national commitment to the underlying reforms. Moreover, by its nature, IMF engagement is more effective at addressing short-term problems of macroeconomic instability and can play only a limited role in promoting longer-term actions to address underlying structural issues. In some countries, governments have used the presence (and conditionality) of the IMF to undertake difficult structural reforms, but these were reforms that the government wanted to carry out. Where the IMF has been less successful is in pushing reforms that the host country government itself does not support. In these cases, good intentions generally remained just that.

In Pakistan, as in many other countries needing IMF support, the decision to ask the IMF for help is typically deferred until a crisis appears imminent. At that point, both the authorities and the IMF staff agree that the immediate focus of the IMF program should be, first and foremost, on arresting the deterioration in macroeconomic imbalances and restoring macroeconomic stability. And in most instances, the programs have been quite successful in doing that. Fiscal and current account imbalances were contained, reserves started to be rebuilt, and confidence in the economy was strengthened, leading to a pick-up in domestic investment and external financing. In parallel to these stabilization measures, the authorities and the IMF staff also usually agreed on a set of plans to address the underlying structural weaknesses. On the fiscal side, this has often comprised targets for increased tax revenues backed up by plans to enhance tax administration or to bring more people into the tax net. This has sometimes been accompanied by plans to reduce losses in public enterprises through tariff policy, better management, or privatization. On the external front, the structural agenda has mainly focused on improvements to the business environment or tariff policy to encourage increased exports.

In the majority of cases, these reforms were not fully implemented, leading to Pakistan abandoning the IMF assistance program before completion. Although each episode and each program are unique, there is a common pattern. In most cases, the initial year of the programs went well, with the government taking the urgent fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate measures necessary to stabilize the economy and restore a degree of confidence. However, in the later years, when the programs moved to tackling some of the underlying structural weaknesses that gave rise to the macroeconomic stress, the government’s ability and political will to follow through waned and, as the crisis-related pressures were also abating at the time, the programs were left to wither.

Sometimes, the IMF continued to support the country when the macroeconomic aggregates—such as the reduction of the fiscal deficit or the buildup of reserves—continued to show the anticipated progress. In these situations, the IMF staff and board have generally adopted an accommodative posture and given the benefit of the doubt to the country authorities, with the IMF board approving continued program funding with “waivers of conditionality.”

Is the availability of IMF financing a disincentive for reform?

It is sometimes asked whether the availability of IMF financing is itself a disincentive to fundamental reforms. Since policymakers know that the IMF will be there with a “bailout” if they run into a macro crisis, the argument goes, there is less of an incentive for them to undertake difficult reforms that would be counter to the interests of powerful stakeholders. Economists refer to this as the “moral hazard” problem. This is a serious argument with a foundation in both economic theory and empirical evidence. The work of respected economists like Michael Bruno has shown that many instances of fundamental economic reforms have been triggered by a major crisis.

The question then becomes whether, given the history of past programs, the IMF should refuse to finance a new program when approached by Pakistan, in the hope that the ensuing crisis would trigger reforms that would obviate the need for subsequent support. This is theoretically a possibility, but it faces intellectual, moral, and practical difficulties that make it unlikely to happen.

Intellectually, it is true that deep crises can lead to deep reforms, but this is not inevitable in any given episode. Reforms are generated by a variety of factors and conditions, and each country context is different. It is equally possible that a deep crisis will simply result in a prolonged period of chaos and stagnation. On a moral plane, the cost of crisis is borne disproportionately by the poor and vulnerable. Millions would fall below the poverty line, and some would suffer permanent damage to welfare and living conditions. It is not evident that any policymaker or international institution has the right to willingly bring about a crisis with such severe consequences for the poor in the uncertain expectation that it will lead to a change in national behavior. On a purely practical level, the IMF was created to help its members facing an imminent financial and economic crisis, and it would not be realistic to expect its staff or board to refuse assistance to a member to teach it a lesson and change its behavior.

Another question is whether the design of IMF programs is flawed in promoting stabilization over growth or structural change. This is a complex topic on which much has been written both by the IMF and by independent observers. However, at the end of the day, the fundamental problem is that a country facing an imminent balance of payments or economic crisis must make (often painful) adjustments to reduce fiscal or external account imbalances. While the pace and scope of these adjustments can be moderated by the additional funding that comes from the IMF, some adjustment remains necessary. The relevant question becomes how to design the adjustment to minimize the negative impact on growth or on the welfare of the more vulnerable sections of society. This requires the engagement of a broader set of policymakers—at both the federal and provincial level—than has sometimes been charged with managing the discussions with the IMF on macroeconomic issues.

Can the future be different?

How can Pakistan break out of the cycle of near-crisis to stabilization, to partial but inadequate structural reform, to buildup of vulnerabilities leading to a new crisis? One suggestion is for Pakistan to embark on a process to develop and agree upon a national economic agenda. A striking feature of successful emerging market countries is that there is a broad consensus around a core economic agenda. Politicians of different parties, private sector leaders, opinion makers, and economic experts all agree on the general direction and content of the economic program. To be sure, there are differences of emphasis on specific policies or on timing, but much of the content enjoys broad support. This has two advantages: first, when the government in power is trying to undertake a difficult reform—privatization or labor market reforms—there will be debate on the method or the manner in which it is carried out, but not on the basic objectives. And second, this broad consensus provides domestic and international investors with a degree of certainty about the future business environment within which they can operate and make long-term investment decisions.

In Pakistan, there is a broad consensus on a national security agenda and on the direction of foreign policy, but when it comes to economics, such a consensus is lacking. The result is that the party in power manages the day-to-day affairs of the economy, and if a crisis is looming, takes steps to restore macroeconomic stability. But it finds it much harder to implement more fundamental reforms. There is no shortage of visions for the future, but there is a disconnect between these visions and the willingness or ability to take the actions required to make the vision a reality.

Pakistan needs a national discussion on what kind of economy it wants to be in 10 years, and then it must agree on the actions needed to get there. This is a broad topic, but even at a narrow macroeconomic level, Pakistan needs a realistic plan of actions that will generate the growth rates that are often set as aspirations rather than objectives. A non-exhaustive list of questions that a national discussion could seek consensus on includes:

- What kind of macroeconomic policies would support Pakistan’s broader growth and distribution objectives?

- What level of inequality is Pakistan comfortable with as a society and what actions is it willing to take to reduce inequality?

- Do Pakistani policymakers want the government to have tax revenues that are close to the emerging market norm of 20 percent of GDP? If so, what would be the composition and structure of those taxes and what kind of revenue administration system would deliver that outcome?

- What is the appropriate level and composition of public spending and how should it be divided between the federal and provincial administrations?

- Where should defense spending be most effectively focused in the context of a tightly constrained overall resource envelope?

- Does the country want to raise exports from under 10 percent of GDP to 25 percent of GDP?

- If so, what actions are needed to change the incentive structure for exporting, and is there broad consensus to implement them?

- Are policymakers willing to support indefinitely a set of loss-making public enterprises, both in the energy sector and outside? If not, can they agree upon a plan for their restructuring and privatization?

- Does the government have a role in fixing administered prices for a variety of products, in effect protecting the producers from market forces? If so, which products and at what cost?

An often-voiced objection to developing a national economic consensus is that it has not happened in many decades and is unlikely to come about now. Perhaps. But it is also the case that attempting to make major structural reforms without such a consensus has failed so far, and there is enough underlying agreement across the political spectrum on core economic fundamentals that, with a degree of political leadership, forging such a consensus should be possible.

The immediate challenge for the next government will be to address a looming balance of payments crisis with a stabilization program that will inevitably impose short-term hardship and reduce growth. However, the more important agenda for Pakistan is to break through to a high-level equilibrium that would avoid the need for repeated stabilization through reforms that leverage the talent of its youth and the entrepreneurial skills of its private sector, and deliver the economic and social performance that its population demands and deserves.

Optimism about Mr. Sanchez should not blind European observers to clear signs of an internal power grab

Optimism about Mr. Sanchez should not blind European observers to clear signs of an internal power grab

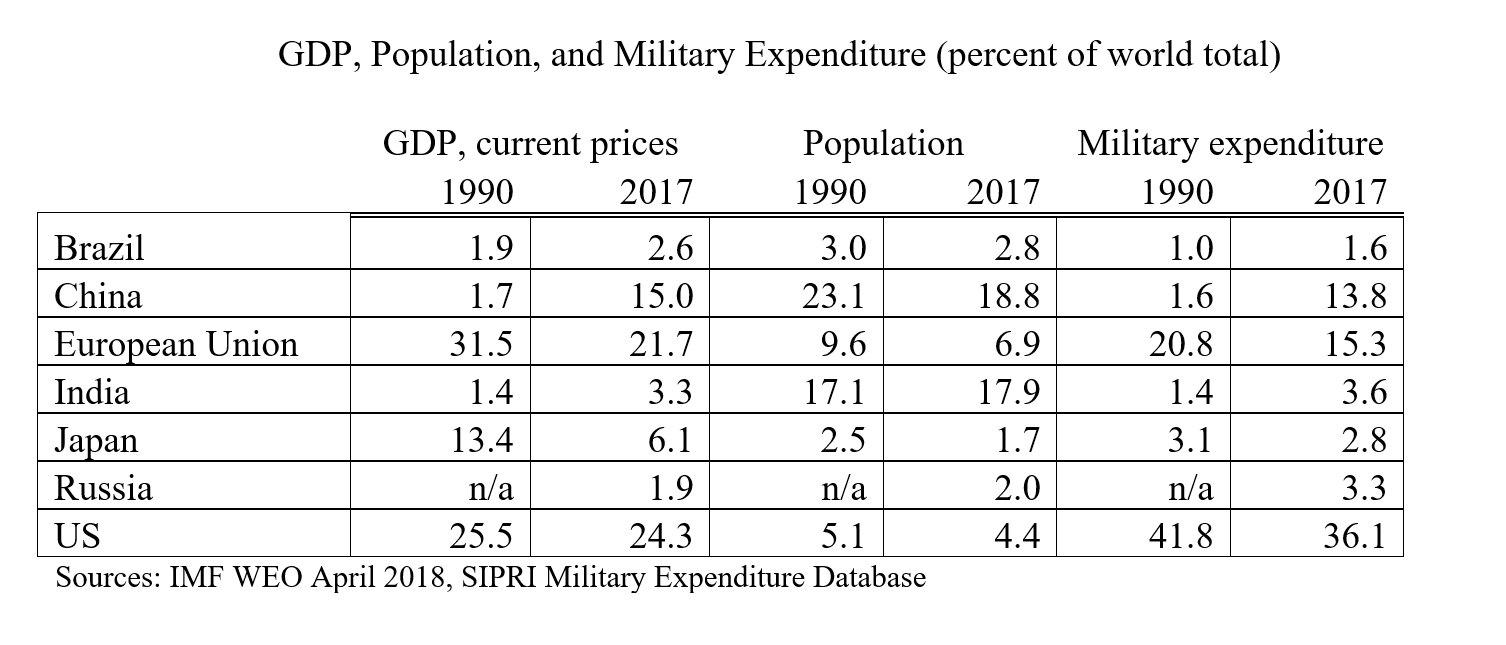

WASHINGTON, DC – From the end of World War II to the mid-2010s, economic globalization progressed relentlessly through expanded trade, proliferating capital flows, faster (and cheaper) communication, and, to a lesser extent, human migration. Yet, even as these linkages have deepened and multiplied, the global economy has remained fundamentally a collection of national economies, each embedded in national politics. This is now changing.

In the democratic countries that have built the market capitalism that dominates the world today, the building blocks of the economy – taxation, public spending, and regulatory frameworks – are enacted by the legislature and interpreted by the legal system. This lends legitimacy to them and the economic activities they facilitate.

But a shift is occurring: global markets already are more important than national markets for small and medium-size countries, and they are approaching that status for large economies. In less than a decade, it will be the huge world market, rather than national markets, that allocates capital, finance, and skilled labor. Many firms will be truly multinational, with headquarters located in one place (probably where tax liabilities can be minimized), production and sales happening largely elsewhere, and managers and workers sourced from all over the world.

The emergence of such a truly global capitalism – a process that, to be sure, is far from complete – means that markets will no longer be embedded in the politics or regulatory systems of various nation-states. If they are to produce desirable outcomes, they will need to be embedded more deeply in – and regulated more effectively by – global institutions.

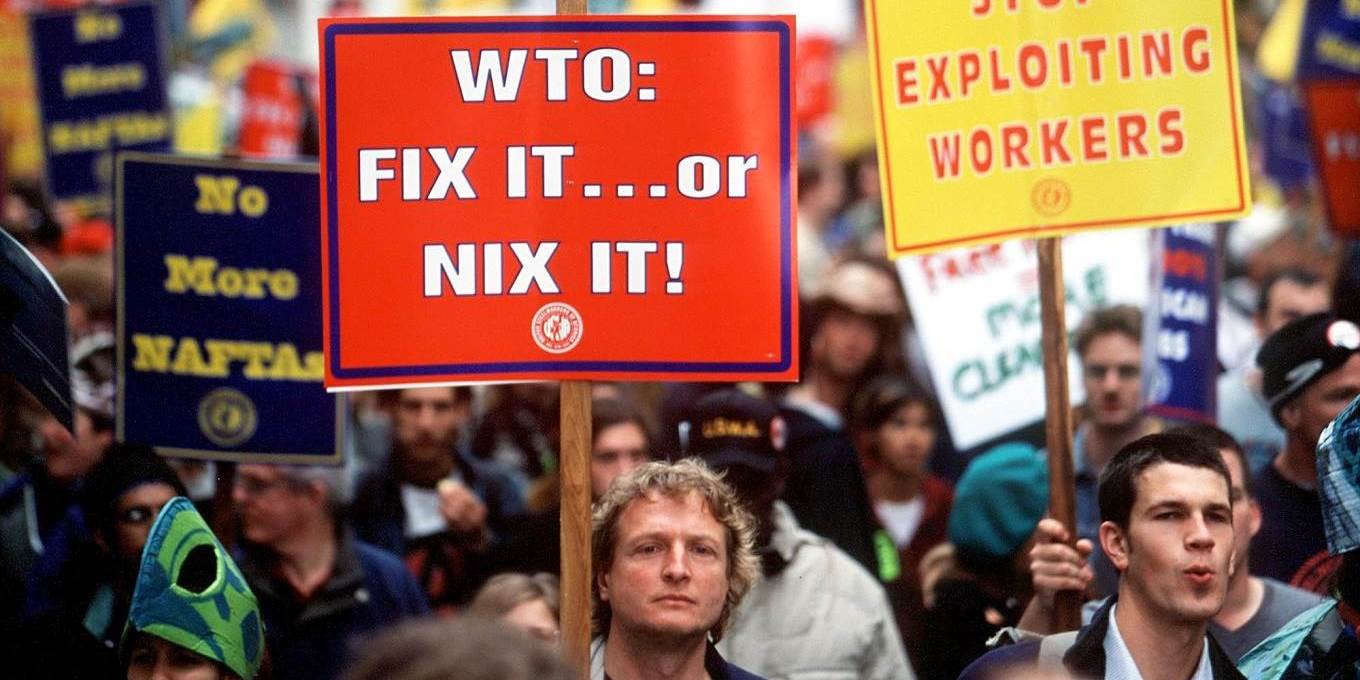

Of course, international economic institutions – from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank to the economic bodies of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization – already exist and have long served as platforms for member states to adopt shared rules. The IMF and the WTO, in particular, have acquired some real regulatory authority in macroeconomic and trade policy, respectively.

Domestic politics were largely eschewed in establishing and sustaining these international institutions. Though treasuries, central banks, and trade ministries – especially of the advanced countries – acted politically, they did so with very little public debate. Even today, the average citizen in the United States, France, or India knows little about what the WTO actually does.

In other words, the emergence of a global market is not embedded in any legitimacy-conferring political process. Multilateral institutions are thus viewed as elitist, making them a political target. This is reminiscent of the European Union’s “democratic deficit,” which has fueled resistance to further integration.

In fact, resistance to global capitalism is also rampant and rising. In particular, US President Donald Trump espouses a kind of “go-it-alone” neo-nationalism. Far from deepening multilateral structures, he wants to dismantle them, dislodging the global market from the regulatory institutions in which it is already only weakly embedded. At both the national and international levels, Trump believes that the less regulation, the better.

The EU, meanwhile, pursues the opposite line. Despite the internal challenges it faces, it continues to try to regulate markets beyond national borders. This year alone, the European Commission has imposed over €5 billion ($5.8 billion) in fines on Alphabet Inc., Google’s parent company, and Qualcomm for breaching antitrust restrictions. And with its General Data Protection Regulation, the EU has sought to tighten restrictions on the use, sharing, and control of personal data.

Because the EU has such a large market, such actions have a far-reaching impact. But when it comes to setting truly international standards, the EU obviously falls short. This has become all the more true with figures like Trump actively working against its efforts and espousing deregulation at a time when the level of global economic interconnectedness demands just the opposite.

Allowing major multinational companies, which are already reaping massive profits and crowding smaller players out of entire industries, to avoid paying much tax does far-reaching damage, not least by exacerbating inequality and weakening public budgets. But such firms can be regulated effectively only through multilateral cooperation. Likewise, the only way to make any headway on combating the effects of climate change is for all countries to work together.

The realities of today’s global economy demand that we make multilateral institutions work. That means not only increasing the clout of existing institutions – here, reform is a prerequisite – but also establishing new institutions, such as a Global Competition Authority. None of this will be possible without a real global political debate.

Of course, the emergence of a global politics has far-reaching potential implications for traditional ideas about democracy, not to mention national sovereignty. At the same time, however, allowing the global market to function without adapted regulation, enacted by legitimate and effective international institutions, would amount to abandoning the essence of democracy.

The challenge ahead has been presented by Harvard economist Dani Rodrik in the form of a trilemma: when it comes to democracy, national sovereignty, and globalization, we can have any two, but never all three. Rodrik advocates less globalization and more democracy. Nationalists like Trump prefer strengthening the nation-state, in ways that could weaken both democracy and globalization, at least in the longer term.

In the medium term, however, further globalization seems unavoidable, meaning that it is the nation-state, and national politics, that must be constrained. One way to lend legitimacy to the new global politics would be to ensure that it is grounded at the local level. This will require local political leaders to adopt a narrative that explains how global problems impact their constituents. Climate change is a successful example of this form of localized global politics.

Whatever institutional arrangements are chosen, ensuring that a new global politics strengthens, rather than undermines, democracy is the central political challenge of the twenty-first century. We can no longer afford to shy away from it.