Publié le 22/06/2018

Propos recueillis par Alexis Lacroix dans L’Express

L’ancien ministre Hubert Védrine et l’historien Alexandre Adler échangent sur le nouvel ordre mondial, et ses menaces.

Hubert Védrine, ancien ministre des Affaires étrangères et spécialiste de politique internationale, signe un livre important, Comptes à rebours (Fayard). Face à lui, l’historien Alexandre Adler, auteur, entre autres, de La Chute de l’empire américain, une charge vibrante contre le trumpisme, paru chez Grasset. Ils dessinent à deux voix les lignes de force d’un mêlée mondiale pleine de périls et d’inconnues.

L’EXPRESS.- Pourquoi parlez-vous, dans votre livre, de “comptes-à-rebours”. Ont-ils commencé et, si oui, depuis quand ?

Hubert VEDRINE. En toile de fond de l’actualité qui nous distrait chaque jour, plusieurs comptes-à-rebours inquiétants, dont les tic-tac s’égrènent, se poursuivent. Or, aucun de ces processus globaux n’est automatiquement favorable à ce que nous sommes : des Occidentaux, des Européens, des Français. D’abord, la démographie. La période qui s’annonce est périlleuse : la juxtaposition d’une Europe qui restera stable, dans le meilleur des cas, et d’une Afrique voisine qui va exploser jusqu’à ce qu’elle soit touchée, elle aussi, par la transition démographique. Indissociable du compte-à-rebours démographique, il y a le compte-à-rebours écologique (climat, biodiversité, océans, forêts, etc.). Il est tout simplement impossible que, demain, 10 milliards d’individus arrivent à coexister sur la planète s’ils persistent à pratiquer le mode de vie et de production occidental et prédateur actuel. Enfin, il y a l’incertitude numérique : panacée ou menace supplémentaire ? Il faut se méfier de l’optimisme technologique quand il est trop simpliste. Progrès nombreux, oui, mais le numérique, avec son horizontalité spontanée, et son anarcho-démocratie, peut contrarier la décision publique, verticale, ou tout thromboser. S’il est évidemment très prometteur, le moment Macron ne suffit pas à nous réconforter, car il est particulier.

Hubert Védrine. afp.com/Lionel Bonaventure

Alexandre ADLER. Vous avez entièrement raison sur ce diagnostic. La question démographique n’est pas séparable des enjeux écologiques, et ceux-ci ne sont pas étanches vis-à-vis de la question du numérique. Toute personne qui n’arrive pas à saisir les interactions entre les trois phénomènes est condamnée à passer à côté de la réalité. De même, en 1947, même de Gaulle escomptait une attaque soviétique et se trompait lourdement. Il aurait dû en rester à son analyse antérieure, selon laquelle il y avait du jeu entre la politique soviétique et la politique américaine, et selon laquelle il y avait encore une marge de manoeuvre pour la France. Les interactions étaient en fait déjà présentes, et les relations occidentalo-soviétiques n’étaient pas figées. Il était possible d’anticiper, sur le plan économique, une évolution en faveur de l’Occident.

H.V.- Mon analyse se concentre en effet sur cette “conjonction” menaçante. Nous sommes défiés par une combinaison potentiellement explosive, au sens chimique du terme, de ces phénomènes. Et pourtant, les élites classiques ont toujours du mal à intégrer l’absolue nécessité d’arrêter le compte-à-rebours écologique ! Quant aux milieux économiques “mondialisateurs”, ils ont trop longtemps cru la géopolitique périmée. Elle est bien là, plus coriace que jamais.

A.A.- Hubert Védrine fait partie des rares esprits qui montrent l’interdépendance de la démographie et de l’écologie, qui sont en train de modifier de manière radicale notre monde. Comment peut-on raisonner sur le prix du pétrole et des matières premières, sans voir la transition énergétique ; un certain nombre de Saoudiens sont plus lucides sur ce point et ont pris acte que la transition écologique a déjà condamné en tendance le prix actuel des hydrocarbures. D’où le caractère, selon eux, indispensable d’investissements productifs en Arabie saoudite même.

H.V.- Oui, ce bouleversement modifiera bientôt le sens même de l’expression “Etat voyou”. Bientôt, l’Etat voyou, ce sera celui qui ne mettant pas une oeuvre une écologisation raisonnable, mettra en péril tous les autres.

Le Moyen Orient est-il l’un des théâtres principaux de ce basculement du monde?

A.A.- Sans aucun doute, à cause de la fin, justement, de l’ère du pétrole. Mais dans le raisonnement d’Hubert, j’intégrerais volontiers la révolution engendrée par une urbanisation massive. Une des voies les plus écologiques pour gérer des ressources rares et pour intégrer le choc démographique que nous allons subir est évidemment l’urbanisation. Le pouvoir des villes est en train de s’affirmer d’une façon inédite à l’échelle de l’Europe. Je vois, par exemple, la façon dont Lyon s’autonomise de Paris en regardant à la fois vers Barcelone et vers Milan. Tout indique notre entrée dans un monde quantique.

Un monde quantique, au sens d’Einstein. C’est-à-dire ?

AA.- Un monde d’incertitude maximale, où il n’y a plus ce paysage stable de sujets attendus. On ne peut plus tabler, par exemple, sur le fait, pour reprendre l’expression consacrée, que “l’Amérique veut”. La caractéristique déroutante d’un monde quantique, c’est que tous les acteurs y sont divisés : ainsi, aujourd’hui, l’Amérique est divisée ; de même, il n’y a pas une, mais deux Russie, et Poutine n’incarne pas la pire ; le Moyen-Orient n’est pas plus uni que l’islam, et j’ajouterais que, s’il existe une exception chinoise – notamment l’ambition de maintenir la solidité de la puissance chinoise -, il existe partout ailleurs une labilité quantique.

H.V.- A raison, Régis Debray écrit que la mondialisation “heureuse” a conduit à la “balkanisation généralisée”. Oui il y a une certaine fragmentation “quantique” des grandes entités, mais ce phénomène touche aussi les entités privées. Voyez les GAFAM : elles détiennent plus de pouvoir que les 3/4 des membres des Nations unies, mais elles entrent dans une zone moins triomphale !

A.A.- Même la mafia s’est atomisée…

H.V.- Quant au Moyen-Orient, ce qui s’y passe confirme malheureusement que le monde en l’absence d’une puissance hégémonique, ne parvient pas à s’ordonner par lui-même. Cela laisse à beaucoup d’acteurs sans scrupules, encouragés par l’impunité du “trumpisme”, la latitude de pousser leurs propres pions. Dans cette région s’entrecroisent, dans une sorte de mêlée généralisée, des conflits classiques entre Etats mais qu’aucun pays (ni l’Egypte, ni la Turquie, ni l’Arabie, ni l’Iran, ni Israël) ne peut gagner complètement, et des entités comme Daesh. Et contrairement à l’époque de Sykes-Picot, les grands de ce monde ne seraient pas davantage en mesure de se mettre d’accord sur une solution, même mauvaise, et de l’imposer…

AA.- Cette “mêlée” est d’autant plus déroutante et irritante pour nous que la France a, dans cette région, un rôle décisif …

HV.- Elle l’a eu longtemps, elle le croit encore un peu, mais ce n’est plus vrai.

AA.- Non, avec les Russes, ce rôle-clé lui revient

Qu’est-ce à dire, exactement, Alexandre Adler ?

AA.- Comme les Russes furent plutôt des vaincus de l’histoire des trente dernière années, nous n’y songeons pas… Et pourtant ! Le père de Hubert Védrine s’est battu pour l’indépendance du Maroc avec un homme extraordinaire que nous admirons tous les deux, et qui était le général Méric. Eh bien, aujourd’hui, le Maroc et l’Algérie sont intensément tournés vers la France, et tous les écrivains algériens qui comptent vivent entre Alger et Paris. En Algérie, la “perestroïka” qui s’annonce avec la disparition de Bouteflika sera française.

Un autre pays est comparable à la France : la Russie, pour qui la sauvegarde de la Syrie est une affaire intérieure. Ainsi, elle est en train de mener une politique pragmatique au Moyen Orient, qui s’avère complètement convergente avec celle de la France, qui, sous l’impulsion de Jean-Yves Le Drian, a consenti de grands sacrifices pour contenir les djihadistes au Sahel. Anglais et Américains ne veulent rien savoir de ce vaste défi géopolitique ; Français et Russes témoignent d’un même souci d’endiguer la destructivité islamiste, ce qui installe une convergence.

H.V.- Nous sommes encore bien loin de cette convergence. Certes, les torts sont partagés, nous avons réveillé par nos erreurs depuis 1992 les pires aspects du système russe, mais cet antagonisme paraît pour le moment sans issue. Même aux pires moments de la guerre froide, à l’époque de menaces beaucoup plus concrètes, de grands dirigeants réalistes avaient osé la détente. Aujourd’hui, nous ne sommes qu’au début du cheminement souhaitable dessiné par Alexandre Adler, si nous y sommes. Mais, peut-être Emmanuel Macron a-t-il parlé de l’avenir avec Poutine ?

Comment tenir l’équilibre entre l’Iran et l’Arabie saoudite, pour une puissance comme la France ?

A.A.- Il n’y a pas d’équilibre à tenir. L’Iran et l’Arabie saoudite sont deux partenaires indispensables pour la France. Mais dans la décision immédiate, le choix d’un camp est indispensable. Et j’approuve tout à fait Jean-Yves Le Drian, qui n’a pas hésité à tirer la barbe des mollahs, et à ce que nous soutenions le cours actuel d’une Arabie saoudite qui se réforme. Mais, à un plus long terme, j’estime que les efforts de Rohani pour réintégrer la communauté internationale doivent être soutenus. Mais nous n’accepterons pas la politique de force en Syrie, dirigée contre l’Occident mais aussi contre la Russie et son influence modératrice ; ne sera pas non plus tolérée la politique d’invasion du dossier yéménite par des ambitions de grandes puissances, de même que le rapprochement irano-turc.

Les Européens ont-ils raison de vivre dans la nostalgie de ce que fut “l’Amérique virgilienne” ?

H.V.- Globalement, quel que soit le sujet, les Européens pèchent par irréalisme. Du coup, face aux dures réalités, ils sont choqués et se réfugient dans les chimères. Cela dit, la chancelière Merkel a déclaré récemment que les Américains étant devenus peu fiables (euphémisme !), il était nécessaire que les Européens s’organisent mieux entre eux. C’est ce que souhaite aussi le Président Macron. Le déclenchement de la guerre commerciale par Trump devrait avoir cet effet. Mais il y a encore du chemin ! Cela dit ce sursaut européen ne passe pas forcément par plus d’intégration au sens classique. Des votes à la majorité, sans veto, dans l’Europe telle qu’elle est, ne conduiraient pas à une Europe-puissance au contraire. C’est un déblocage mental pour une ré-accepation préalable et la notion de puissance qui est nécessaire au préalable.

A.A.- Il nous faut renoncer à toute influence ultérieure avec les Anglais, lesquels ne feront pas retour à l’Europe. Pour l’heure, Macron affiche une position personnelle d’adhésion à la France, et sa première adhésion au parti socialiste s’était d’ailleurs déroulée dans le giron idéologique du chevènementisme. Les objectifs européens qu’il affiche ne sauraient donc en aucun cas s’accompagner d’une minoration des intérêts français. A titre personnel, j’apprécierais qu’il ait plus de souplesse à l’égard d’une opinion allemande elle-même traversée par de nombreux remous. Il a mangé son pain blanc avec Angela Merkel, qui va, je crois, devoir se retirer, ce qui explique les lauriers qu’on lui tresse !

H.V. – Ce qui est très intéressant, chez Emmanuel Macron, c’est la synthèse dynamique en cours entre son européisme philosophique de départ, l’objectif d’une Europe qui doit protéger, et les projets.

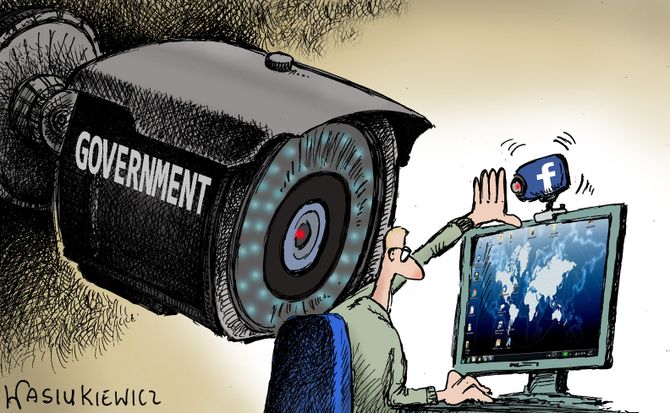

The danger of misuse by governments is much bigger; they have the power to introduce repressive measures

The danger of misuse by governments is much bigger; they have the power to introduce repressive measures

CAMBRIDGE – For years, political leaders such as former US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta have warned of the danger of a “cyber Pearl Harbor.” We have known for some time that potential adversaries have installed malicious software in our electricity grid. Suddenly the power could go out in large regions, causing economic disruption, havoc, and death. Russia used such an attack in December 2015 in its hybrid warfare against Ukraine, though for only a few hours. Earlier, in 2008, Russia used cyber attacks to disrupt the government of Georgia’s efforts to defend against Russian troops.

Thus far, however, cyber weapons seem to be more useful for signaling or sowing confusion than for physical destruction – more a support weapon than a means to clinch victory. Millions of intrusions into other countries’ networks occur each year, but only a half-dozen or so have done significant physical (as opposed to economic and political) damage. As Robert Schmidle, Michael Sulmeyer, and Ben Buchanan put it, “No one has ever been killed by a cyber capability.”

US doctrine is to respond to a cyber attack with any weapon, in proportion to the physical damage caused, based on the insistence that international law – including the right to self-defense – applies to cyber conflicts. Given that the lights have not gone out, maybe this deterrent posture has worked.

Then again, maybe we are looking in the wrong place, and the real danger is not major physical damage but conflict in the gray zone of hostility below the threshold of conventional warfare. In 2013, Russian chief of the general staff Valery Gerasimov described a doctrine for hybrid warfare that blends conventional weapons, economic coercion, information operations, and cyber attacks.

The use of information to confuse and divide an enemy was widely practiced during the Cold War. What is new is not the basic model, but the high speed and low cost of spreading disinformation. Electrons are faster, cheaper, safer, and more deniable than spies carrying around bags of money and secrets.

If Russian President Vladimir Putin sees his country as locked in a struggle with the United States but is deterred from using high levels of force by the risk of nuclear war, then perhaps cyber is the “perfect weapon.” That is the title of an important new book by New York Times reporter David Sanger, who argues that beyond being “used to undermine more than banks, databases, and electrical grids,” cyberattacks “can be used to fray the civic threads that hold together democracy itself.”

Russia’s cyber interference in the 2016 American presidential election was innovative. Not only did Russian intelligence agencies hack into the email of the Democratic National Committee and dribble out the results through Wikileaks and other outlets to shape the American news agenda; they also used US-based social-media platforms to spread false news and galvanize opposing groups of Americans. Hacking is illegal, but using social media to sow confusion is not. The brilliance of the Russian innovation in information warfare was to combine existing technologies with a degree of deniability that remained just below the threshold of overt attack.

US intelligence agencies alerted President Barack Obama of the Russian tactics, and he warned Putin of adverse consequences when the two met in September 2016. But Obama was reluctant to call out Russia publicly or to take strong actions for fear that Russia would escalate by attacking election machinery or voting rolls and jeopardize the expected victory of Hillary Clinton. After the election, Obama went public and expelled Russian spies and closed some diplomatic facilities, but the weakness of the US response undercut any deterrent effect. And because President Donald Trump has treated the issue as a political challenge to the legitimacy of his victory, his administration also failed to take strong steps.

Countering this new weapon requires a strategy to organize a broad national response that includes all government agencies and emphasizes more effective deterrence. Punishment can be meted out within the cyber domain by tailored reprisals, and across domains by applying stronger economic and personal sanctions. We also need deterrence by denial – making the attacker’s work more costly than the value of the benefits to be reaped.

There are many ways to make the US a tougher and more resilient target. Steps include training state and local election officials; requiring a paper trail as a back-up to electronic voting machines; encouraging campaigns and parties to improve basic cyber hygiene such as encryption and two-factor authentication; working with companies to exclude social media bots; requiring identification of the sources of political advertisements (as now occurs on television); outlawing foreign political advertising; promoting independent fact-checking; and improving the public’s media literacy. Such measures helped to limit the success of Russian intervention in the 2017 French presidential election.

Diplomacy might also play a role. Even when the US and the Soviet Union were bitter ideological enemies during the Cold War, they were able to negotiate agreements. Given the authoritarian nature of the Russian political system, it could be meaningless to agree not to interfere in Russian elections. Nonetheless, it might be possible to establish rules that limit the intensity and frequency of information attacks. During the Cold War, the two sides did not kill each other’s spies, and the Incidents at Sea Agreement limited the level of harassment involved in close naval surveillance. Today, such agreements seem unlikely, but they are worth exploring in the future.

Above all, the US must demonstrate that cyber attacks and manipulation of social media will incur costs and thus not remain the perfect weapon for warfare below the level of armed conflict.